- Home

- Laurie R. King

The Bones of Paris Page 8

The Bones of Paris Read online

Page 8

“Very Breughel.”

“Dozens of artists have addressed the theme, from its beginnings at the time of the Black Death. Bosch, of course. There’s a book of Holbein woodcuts with captions about each victim, seized by Death and shown the steps of the Dance.”

“Death and dancing. Sounds like Montmartre on a Saturday night.”

“So are you interested?”

“I don’t know much about popes and plowmen.”

“Those were the fourteenth century. Ours would see mayors and street-sweepers, movie stars and newspaper boys.”

“High-society blondes. Negro trumpet players.”

“Precisely.”

“Could still have the prostitutes. They probably haven’t changed much.”

“You may be right.”

“Would the thing have to be painted?”

“Painting, collage, photographs. Didi Moreau is looking into the possibility of doing one made from human bones. Each must fit onto a twelve-by-fifteen-foot panel, with the dimensions of the figures life-sized to make the end result more seamless.”

“Linking together. Ah—is that why you had us playing ‘exquisite corpses’?”

“Precisely.”

“And the theme is Death’s Dance.”

“Yes.”

“You care how graphic they are? How realistic?”

“Chaim Soutine is doing a panel along the lines of his carcass paintings.”

“Well, that’s about as graphic as you can get. In that case, sure, I’d be interested.”

“I will have my assistant send you a contract. And may I say, M. Ray, how much I look forward to your panel?”

“It’ll be a killer, all right.”

FOURTEEN

“C’EST MORTE,” STUYVESANT said.

The bartender gave the American one of those wide French nods of shared desolation as he placed the brimming blonde on the zinc bar.

“Ira mieux, mon ami,” he said, and followed his damp cloth down the long bar to his other thirsty customers.

Harris Stuyvesant looked glumly at the glass. It was ten at night, and he didn’t think it was going to get better. Paris was dead. The heat had killed it.

He’d known how it would be before he left Berlin—knew that in August, the city’s tailors and hat-makers and butchers all closed their shops to escape the heat. He just hadn’t thought that the vacances could stretch this far into September—theaters slow to open, the rich lingering in the south. Even the butchers were still in the mountains, settled on their broad derrières with a glass of vin ordinaire, casting their professional eyes across the grazing moutons while they tried to decide if they could stretch out their vacances until the heat broke down by the Seine.

Ridiculous. Ten days into the new month, and it seemed that only the dirt-poor locals and the ever-naïve tourist wandered the sweltering streets. Pip’s friends—those he’d been able to track down from her address book before it grew too late for doorbell-ringing—seemed to be off with all the other scrubbed-face leeches, in Spain playing bullfighter like Hemingway. In the South of France drinking like the Fitzgeralds. In the States raising money like, well, everyone else.

The bartender—“François, call me Frank”—brought his cloth back to Stuyvesant’s end of the bar.

“You have not found your Peep,” he said, with professional sympathy. Old women and bartenders did love to gossip.

“Nope. Saturday and Sunday here and in the Quarter, yesterday in Saint-Germain, and nothing. I figured I might as well come back here tonight.” In a move so well practiced his hand did it without consulting his brain, Stuyvesant slid the snapshot from his breast pocket and snapped it down next to his glass, facing the other man.

Frank had seen it before—he was one of the first Stuyvesant showed it to on Saturday—but still he leaned over to take a closer look at the grinning blonde with the trace of wariness about the eyes.

“Pretty girl,” Frank commented. “A … friend?”

“Just a job,” he lied.

“Her eyes, they are blue, n’est ce pas?”

“Green,” Stuyvesant corrected, then immediately reversed himself. “No, you’re right—blue. Sorry. Blue eyes, blonde hair, five-six, slim, slightly chipped left upper incisor, speaks pretty good French, did a year of college, likes books, music, daisies, and chocolate.” The bartender was unlikely to have seen evidence of the broken arm and the burn scar. Unless he, too, was a painter. Or a coroner.

The two men scowled at the image, Frank searching his memory, Stuyvesant thinking that, since this no longer looked to be a quick job, he’d better have copies made before the photo got any more ragged.

“I thought I’d found a lead,” he told the bartender, “but it turned out to be another American girl.”

“There are so many,” Frank said mournfully. He seemed to like Americans—their dollars, anyway—but Stuyvesant figured the USA’s conquest of Paris must be getting annoying. Maybe the early wave was good for a laugh, after the War, but as Sylvia had said, the actual writers and painters were now outnumbered by hangers-on, common criminals, chronic alcoholics, and open-mouthed rubberneckers. God knows he found it a damned nuisance, and it wasn’t even his city.

He shook his head in a return of sympathy. “If the stock market keeps on like this, pretty soon somebody’ll build a link between the subway and the Métro.”

“That will be the day I retire,” Frank said, sounding grim. He raised his eyes from the picture of the missing girl. “You have been to, you know …?”

“The morgue? What the hell is it with everyone? She’s just missing, not dead. She’s probably gone back to America.”

“Some would say that was the same thing, Monsieur.”

“Hah, hah.”

“Mais non, Monsieur—in fact I meant, have you been to the police?”

“Oh. Well, yes, them, too. And the American Embassy. None of them were very interested in one more missing Flapper. And last night I went through Saint-Germain, in case her blood was a little rich for the likes of Montparnasse. Nothing.” He made a mental note to go back to the Embassy when he had copies of the photo to leave.

A group of Americans came in and Frank went to serve them. Stuyvesant watched idly, elbow propped on the bar. Three men, one from Brooklyn, two sounding more like Jersey—painters, judging by the state of their clothes, the New Yorker maybe a sculptor. Artists tended to take the first shift in Montparnasse’s night-life, finishing work when the sunlight faded. The Quarter’s writers, on the other hand, were probably just thinking about their breakfast.

This trio were in the midst of some urgent discussion, and Stuyvesant listened with half an ear. Art talk, the older of the two painters—a man wearing a paint-spattered suit, no neck-tie, and sandals on his horny-looking feet—declaring vehemently that no matter how much money they brought in (whatever “they” might be) they weren’t art, just junk in a frame, while the sculptor (corduroy trousers, flax blouse, and a single heavy turquoise earring that dangled wildly with every gesture) took the opposite position with equal certainty, blathering on about something called “readymades,” although it didn’t seem to have much to do with clothing. The third man—shorter, younger, dressed in blue jeans and what looked like a Romanian peasant shirt—nursed his drink for a while before venturing an opinion that the titty displays were certainly intriguing, and did seem to have that disturbing frisson of visceral excitement (Jesus: who talked like that? And sure, naked girls could be artistic, but he wasn’t sure how they might be called “junk in a frame.”) that a person felt only in the presence of True Art—

His fellow New Yorker would have none of it, and their voices climbed until Frank touched the sculptor’s wrist and suggested, perhaps outside?

They turned to the door, seeming well accustomed to the request. Before they got there, the argument broke off as they stood back to let a pair of women come in. Frank’s waiter followed the two, took their order, and came back smiling: they were re

gulars. One looked familiar, and when the waiter had given the order—white wine and a fancy cocktail—Stuyvesant stopped him.

“Those two who came in? One of them models, for artists, doesn’t she?”

“That’s not all she does for artists, Monsieur.”

Stuyvesant returned his grin, but stayed where he was. No point asking a pair of hard-working girls anything until they’d had their first drink.

Instead, he rotated the picture on the bar, studying the crooked smile and untidy blonde head. As Frank said, there were a lot of American girls here in gay Paree. The crazy exchange rate made it as cheap for women to live here as it did men—nearly as cheap—and although fewer girls might come to experiment with painting or writing, they sure came to experiment. In the process, many of them discovered that girls were every bit as good at having fun as the boys were.

Like Pip Crosby.

He took out the other photo and put on his glasses, comparing the two versions of the girl he’d known. The snapshot that had seemed at first the very image of an expatriate good-time girl seemed to have darkened under the influence of the other photo, as if the character had leaked across the pages.

The Man Ray photo made Pip look older and more mysterious—but then the guy was an artist, a clever one. He could probably make a salt cellar look Deep. The snapshot showed a young girl with wind in her hair. Maybe her smile was a bit … knowing, but was there really mistrust in her eyes?

And why the hell did he persist in thinking of them as green? Oh, he knew why, but damn it, Pip Crosby’s eyes were blue.

Irritably, he caught up the squares of paper and went back to work.

The models’ table had a pair of extra chairs, just in case friends showed up, and they were happy to let him claim one. He said hello, broke the ice for a minute, and before they could begin to wonder if he had something in mind with one (or both) of them, he took out the snapshot.

The older one didn’t recognize Pip, but made it clear that she would be pleased to talk about the picture for a while, if the American wished to buy her another drink. He obliged, and when the drinks were on the table the younger one asked to see the picture again. She held it close to her eyes, squinting a little: he’d never yet seen a French woman in glasses.

“Connaissez lui?” he asked.

She shook her head, reluctantly. “I thought perhaps, but no. It is that she looks like a girl who used to come here, oh, two years ago? Three?” She consulted with her friend for a while in rapid-fire French, and while the details may have passed Stuyvesant by, he could tell they were talking about a singer named Mimi who had lived in Paris for a while. Finally, she turned back to Stuyvesant. “The picture made me think of someone, but it is not her.”

“Her name was Mimi?”

“We called her that, but I don’t think—”

“Elle s’appelait Marie,” the older one interrupted.

“Non,” the first protested. “Michèle.”

“Michèle? Pas du tout. Mais, peût-être Martine?”

The two peppered the air with various names starting with M, but the matter wasn’t helped by the surname also beginning with an M. Michelle? Michaud?

He thanked them, and moved on to the next table, and the next.

The place was filling up, and the stink of unwashed bodies was doing battle against the cigarette smoke, and winning. Gratefully, he finished his round of the tables and escaped to the terrace, where the smoke was somewhat diluted.

It took some doing to get the attention of the three artists, now hunched over an iron table under the trees, but they either didn’t know Pip, or they were unwilling to detach themselves from the argument to really look at the photograph.

So he went back to the bar and asked Frank to send them a round of drinks. On the waiter’s heels, he pulled up a chair and sat.

“Evening, gentlemen,” he said. “Mind if I join you?”

The trio had not been warned about Greeks and gifts, because they didn’t bother with introductions, just took the full glasses and incorporated their benefactor into the conversation—or, argument. The topic had moved on from displays of women’s breasts to a consideration of modern film, although Stuyvesant thought the two might not be unrelated.

He was waiting for a break in the conversation to pull Pip out of his pocket, when a name made his ears twitch.

“—hired Man Ray to do a film of his house-guests, down in Hyères—Provence, you know? Sounds like a piece of junk to me.” This was the older New Yorker who had dismissed the “titty displays.” A man with a limited critical vocabulary.

“C’mon, that Sea Star movie was a work of genius,” the Jersey sculptor argued.

“Oh, sure, but basically Ray’s just a fashion photographer. If Noailles wanted art rather than a home movie, he’d have asked Buñuel.”

“Who’s Noweye?” the younger painter asked.

“Noailles. Viscount Charles de Noailles,” the sculptor explained. “He and his wife are patrons of the arts.”

“Hey, can I get me one of them?”

“You wish.”

The critic cut in, “He’s mostly interested in film. You need the other one, the guy they call Le Comte—he’s newer to the game, and he’s got a lot of cash to throw around. But neither of them are just patrons. If you watch ’em closely, they’re damned clever. Like that Stein woman—she’s got to have a small fortune on her walls by now.”

“Yeah, you just wish she’d discovered you,” the sculptor jeered.

The snort the younger man gave as reaction made the critic’s face go red. Stuyvesant interrupted with the Man Ray photo.

None of the three knew Pip, although two of them agreed they’d like to. Stuyvesant left before the discussion grew unbearably raunchy and moved to the next terrace.

One advantage of this tightly-knit American community was that it was tight, in both senses. A person found the same faces drinking at the same watering-holes: Coupole, Rotonde, Dôme, the Select, the Jockey, the Dingo, with dozens of smaller places tucked away on the sides—all within convenient staggering distance of that physical and spiritual center of Montparnasse, the Carrefour Vavin. Now a busy intersection, Vavin was originally a rubble heap that Mediaeval students had jokingly dubbed “Mount Parnassus.” The sacred home of Greek Muses became the Parisian home for wine, women, and bad poetry—until eighteenth century city planners flattened the mound in the interest of traffic flow, leaving only the name, and the attitudes.

One disadvantage of this tight community was simple numbers. Take the Coupole: on a busy night, two or three thousand people would cram inside. It could take hours to work your way through the upstairs, the downstairs, and the broad terrace, around the bar, the restaurant, and the dance hall. And that was just one place. The Dôme now had a bar tacked onto it, the Americaine, that was nearly as bad, and although people tended to have their favorite haunts, they also migrated from one terrace to the next.

Tonight, Stuyvesant’s conversation with the Americans gave him an approach: starting at the Coupole bar, he talked movies, of the artistic variety.

It turned out to be a productive entrée into Montparnasse café society. Everyone had an opinion; every second person was either working on a film or considering it. All had recommendations, pro and con, and if he’d tried to see all the pictures that were mentioned, he would have been staring at silver screens until Christmas.

But certain names cropped up time and again, and certain titles: Clair and Picabia, Buñuel and Dalí, Epstein and Dulac, and above all, Man Ray. “Manifesto of the absurd” was bandied about, and “dreamlike sequences” and “the tyranny of the conscious mind.” Un Chien Andalou (which was not about a dog, nor was it set in Andalusia); L’Étoile de Mer (which was not about sea stars, although it did in fact have a sea star in it, briefly); La Coquille et le Clergyman (which had both a shell and a priest, and therefore seemed to be regarded with less respect in this world of sur-reality, just as the “titty display” man wa

s rendered dubious by having actually sold his work).

A couple hours of this, and Stuyvesant was tempted to rise up and overturn the tables—but if he did, the ensuing debate as to the Meaning of his Act might drive him to pound someone’s face in. Instead, he rose up and left a number of conversations.

To his mild surprise, he went all night without spotting Lulu. If she’d appeared, he might have forgotten how tired he was after a long day of cops and bluestockings, but that brassy hair did not catch his eye or that strident voice his ear. To be honest, he wasn’t entirely unhappy. A quiet night would not go unwelcome, and the bank notes she slipped from his wallet—lifting money rather than asking: Lulu liked to think of herself as an amateur—were beginning to add up.

So he walked along to the pub-like comfort of the Falstaff and let Jimmy pour him a glass of his best Scotch. Jimmy Charters had been a British flyweight boxer, and anyone who put on the gloves was a friend of his. Fortunately, Ernest Hemingway wasn’t there.

Jimmy didn’t recognize Pip Crosby.

“Want to leave the picture on the bar?” he asked. “See if anyone knows her?”

“I’ll do that tomorrow—the photographers have been swamped with rolls of film from vacances.”

“Yep, it’s rentrée. Things’ll pick up now.”

“I guess.”

“But not right now. I’m afraid it’s closing time, my friend. Time for you to move on to the Select.”

“Nah, I’ve had enough of plastered Yanks. See you tomorrow, Jimmy.”

“Good luck with your girl.”

Stuyvesant stood on rue Montparnasse and lit a cigarette, feeling the girl in his breast pocket. Feeling the weight of the day.

“Pip, sweetheart, I’m all fagged out. I’ll try again tomorrow.”

FIFTEEN

AS STUYVESANT CAME to the rue Vavin, he waited for his feet to turn the corner towards the Hotel Benoit. They did not. The night felt soft after the harsh day, and about the last thing he felt like was settling onto that hard, solitary mattress with Sylvia Beach’s detective story on his belly and Pip’s reproachful snapshot on the desk.

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

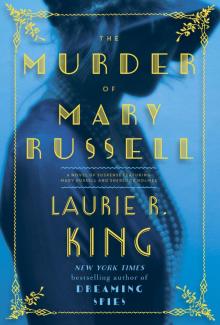

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

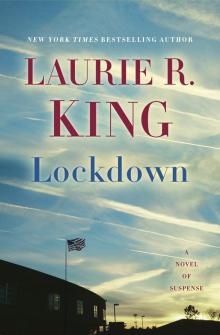

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

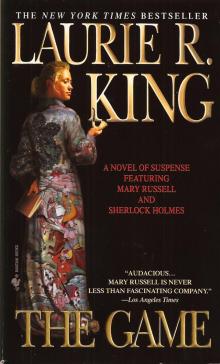

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

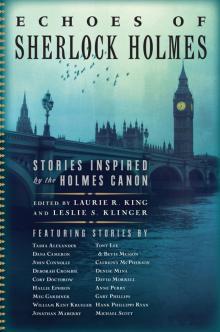

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

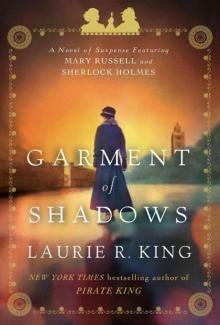

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1