- Home

- Laurie R. King

A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock Read online

A Study in Sherlock

Laurie R. King

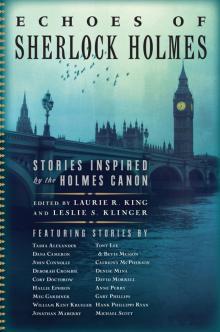

BESTSELLING AUTHORS GO HOLMES--IN AN IRRESISTIBLE NEW COLLECTION edited by award-winning Sherlockians Laurie R. King and Leslie S. Klinger

Neil Gaiman. Laura Lippman. Lee Child. These are just three of eighteen superstar authors who provide fascinating, thrilling, and utterly original perspectives on Sherlock Holmes in this one-of-a-kind book. These modern masters place the sleuth in suspenseful new situations, create characters who solve Holmesian mysteries, contemplate Holmes in his later years, fill gaps in the Sherlock Holmes Canon, and reveal their own personal obsessions with the Great Detective.

Thomas Perry, for example, has Dr. Watson tell his tale, in a virtuoso work of alternate history that finds President McKinley approaching the sleuth with a disturbing request; Lee Child sends an FBI agent to investigate a crime near today's Baker Street--only to get a twenty-first-century shock; Jacqueline Winspear spins a story of a plucky boy inspired by the...

CONTENTS

AN INTRODUCTION

Laurie R. King and Leslie S. Klinger

YOU’D BETTER GO IN DISGUISE

Alan Bradley

AS TO “AN EXACT KNOWLEDGE OF LONDON”

Tony Broadbent

THE MEN WITH THE TWISTED LIPS

S. J. Rozan

THE ADVENTURE OF THE PURLOINED PAGET

Phillip Margolin and Jerry Margolin

THE BONE-HEADED LEAGUE

Lee Child

THE STARTLING EVENTS IN THE ELECTRIFIED CITY

Thomas Perry

THE CASE OF DEATH AND HONEY

Neil Gaiman

A TRIUMPH OF LOGIC

Gayle Lynds and John Sheldon

THE LAST OF SHEILA-LOCKE HOLMES

Laura Lippman

THE ADVENTURE OF THE CONCERT PIANIST

Margaret Maron

THE SHADOW NOT CAST

Lionel Chetwynd

THE EYAK INTERPRETER

Dana Stabenow

THE CASE THAT HOLMES LOST

Charles Todd

THE IMITATOR

Jan Burke

A SPOT OF DETECTION

Jacqueline Winspear

A STUDY IN SHERLOCK: AFTERWORD

A Leslie S. Klinger/Mary Russell Twinterview (with Laurie R. King)

AN INTRODUCTION

Laurie R. King and Leslie S. Klinger

Only true genius can produce an invention, or a hero, that fills a gaping hole in our lives we never knew—never even suspected—was there. For millennia, we were perfectly content with pen and paper; then e-mail was introduced and now no one can live without it. Paintings and lithographs held all the rich vocabulary of visual creation—until photography became our native tongue. And we had a whole raft of heroes to tell stories about: why on earth would we need a self-described “consulting detective” with misanthropic attitudes and unsavory habits?

But one day in 1887, Arthur Conan Doyle sat down to write a tale of an odd young man with peculiar skills and changed the world. A Study in Scarlet is indeed a young man’s story, packed to overflowing with Romantic Adventure and startling ideas, with thrilling lines (lines a modern editor might blue-pencil as melodramatic) such as “There’s the scarlet thread of murder running through the colourless skein of life, and our duty is to unravel it, and isolate it, and expose every inch of it.”

In no time at all, an entire industry of homages and satires, pastiches and parodies sprang up around Sherlock Holmes. Holmes was imagined in a thousand non-Doylean manifestations: married; in exotic climes; paired with historical and literary figures; made younger, older, taller, shorter, more robotic, more emotional, nearly every variation conceivable. Conan Doyle himself wrote non-Holmes stories that were yet openly patterned on the character. That previously unsuspected gaping hole in our lives (the size and import of which Sir Arthur refused to acknowledge) proved to bear the shape of nothing short of an archetype: a modern-day knight errant; a man whose passion for righting wrongs is mistaken for a cold intellectual curiosity; a tortured hero with but a single friend; a man who never lived “and so can never die,” who is more alive today than any other resident of the Victorian Age, including Victoria herself.

The tales in this volume show eighteen top writers exploring the contours and boundaries of that archetype, playing with the ideas of how this Platonic ideal of a detecting hero might look in different situations, wearing a variety of faces. Some recount untold adventures of the Master Detective; others look at him from fresh perspectives; still others listen to the echoes of his passing.

All are stories inspired by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and his first study in Sherlock.

Laurie R. King is the award-winning (Edgar, Creasey, Agatha, Nero, Lambda, Macavity) and bestselling author of a score of crime novels, half of them featuring “the world’s greatest detective—and her husband, Sherlock Holmes.” Mary Russell (The Beekeeper’s Apprentice; Pirate King) has been described as a young, female, twentieth-century Holmes, a gent whom she finds wandering through 1915 Sussex looking for bees and promptly insults. King’s temerity was rewarded by induction into the Baker Street Irregulars, where she was put to work editing Holmes-related books, both fiction and non-, by her Irregular betters, in a thinly disguised attempt to keep her from writing more Russellian novels. Her books and a whole lot of somewhat related academic material can be found at www.LaurieRKing.com.

Leslie S. Klinger is the Edgar-winning editor of The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, a collection of the entire Sherlock Holmes Canon with an almost endless quantity of footnotes and appendices. He also edited the highly regarded The New Annotated Dracula and numerous anthologies of Victorian detective and vampire fiction and criticism. Working with Neil Gaiman, he is currently editing The Annotated Sandman for DC Comics. Klinger is a member of the Baker Street Irregulars and teaches for UCLA Extension on Holmes, Dracula, and the Victorian world. A lawyer by day, Klinger lives in Los Angeles with his wife, dog, and three cats. He first met Sherlock Holmes and his world in 1968, while attending law school, through the pages of William S. Baring-Gould’s 1967 classic The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, and was hooked for life. This anthology is the result of discovering that many of his seemingly normal writer-friends shared his passion for the Holmes stories.

YOU’D BETTER GO IN DISGUISE

Alan Bradley

How long had he been watching me? I wondered.

I had been standing for perhaps a quarter of an hour, gazing idly at the little boys in sailor suits and their sisters in pinafores, all of whom, watched over by a small army of nannies and a handful of mothers, waded like diminutive giants among their toy sailing boats in the Serpentine.

A sudden breeze had sprung up, scattering the fallen leaves and bringing the slightest of chills to an otherwise idyllic autumn afternoon. I shivered and turned up my collar, the hairs at the back of my neck bristling against my jacket.

To be precise, the pressure of my collar put a stop to the bristling which, since I had not noticed it until that moment, made the feeling all that much more peculiar.

Perhaps it was because I had, the previous week, attended Professor Malabar’s demonstration at the Palladium. His uncanny experiments in the world of the unseen were sufficient to give pause to even the greatest of sceptics, among whom, most assuredly, I do not count myself.

I must admit at the outset to an unshakeable belief in the theory that there is a force which emanates from the eye of a watcher that is detectable by some as-yet-undiscovered sensor at the back of the neck of the person being watched; a phenomenon which, I am furthermore convinced, is caused by a specialized realm of magnetism whose principles are not yet fully understood by science.

In short, I knew that I wa

s being stared at, a fact which, in itself, is not necessarily without pleasure. What, for example, if one of those nattily uniformed nannies had her eye upon me? Even though I was presently more conservative than I once had been, I was keenly aware that I still cut rather a remarkable figure. At least, when I chose to.

I turned slowly, taking care to pitch my gaze above the heads of the governesses, but by the time I had turned through a casual half circle they were every one engaged again in gossip or absorbed in the pages of a book.

I studied them intently, paying close attention to all but one, who sat primly on a park bench, her head bowed, as if in silent prayer.

It was then that I spotted him: just beyond the swans; just beyond a tin toy Unterseeboot.

He was sitting quietly on a bench, his hands folded in his lap, his polished boots forming a carpenter’s square upon the gravelled path. A solicitor’s clerk, I should have thought, although his ascetic gauntness did not without contradiction suggest one who laboured in the law.

Even though he wanted not to be seen (a fact which, as a master of that art myself, I recognized at once), his eye, paradoxically all-seeing, was the eye of an eagle: hard, cold, and objective.

To my horror, I realized that my legs were propelling me inexorably towards the stranger and his bench, as if he had summoned me by means of some occult wireless device.

I found myself standing before him.

“A fine day,” he said, in a voice which might have been at home on the Shakespearean stage, and yet which, for all its resonance, struck a false note.

“One smells the city after the rain,” he went on, “for better or for worse.”

I smiled politely, my instincts pleading with me not to strike up a conversation with an over-chatty stranger.

He shifted himself sideways on the bench, touching the wooden seat with long fingers.

“Please sit,” he said, and I obeyed.

I pulled out a cigarette case, selected one, and patted my pockets for a match. As if by magic a Lucifer appeared at his fingertips, and, solicitously, he lit me up.

I offered him the open case, but he brushed it away with a swift gesture of polite refusal. My exhaled smoke hung heavily in the autumn air.

“I perceive you are attempting to give up the noxious weed.”

I must have looked taken aback.

“The smell of bergamot,” he said, “is a dead giveaway. Oswego tea, they call it in America, where they drink an infusion of the stuff for no other reason than pleasure. Have you been to America?”

“Not in some time,” I said.

“Ah.” He nodded. “Just as I thought.”

“You seem to be a very observant person,” I ventured.

“I try to keep my hand in,” he said, “although it doesn’t come as easily as it did in my salad days. Odd, isn’t it, how, as they gain experience, the senses become blunted. One must keep them up by making a game of it, like the boy, Kim, in Kipling. Do you enjoy Kipling?”

I was tempted to reply with that exhausted old wheeze, I don’t know, I’ve never kippled, but something told me (that strange sense again) to keep it to myself.

“I haven’t read him for years,” I said.

“A singular person, Kipling. Remarkable, is it not, that a man with such weakened eyes should write so much about the sense of sight?”

“Compensation, perhaps,” I suggested.

“Ha! An alienist! You are a follower of Freud.”

Damn the fellow. Next thing I knew he’d be asking me to pick a card and telling me my auntie’s telephone number.

I gave him half a nod.

“Just so,” he said. “I perceived by your boots that you have been in Vienna. The soles of Herr Stockinger are unmistakable.”

I turned and, for the first time, sized the man up. He wore a tight-fitting jacket and ragged trousers, an open collar with a red scarf at his throat, and on his head, a tram conductor’s cap with the number 309 engraved on a brass badge.

Not a workman—no, too old for that, but someone who wanted to be taken for a workman. An insurance investigator, perhaps, and with that thought my heart ran suddenly cold.

“You must come here often,” I said, giving him back a taste of his own, “to guess out the occupations of strangers. Bit of a game with you, is it?”

His brow wrinkled.

“Game? There are no games on the battlefield of life, Mr.—”

“De Voors,” I said, blurting out the first thing that came to mind.

“Ah! De Voors. Dutch, then.”

It was not so much a question as a statement—as if he were ticking off an internal checklist.

“Yes,” I said. “Originally.”

“Do you speak the language?”

“No.”

“As I suspected. The labials are not formed in that direction.”

“See here, Mister—”

“Montague,” he said, seizing my hand and giving it a hearty shake.

Why did I have the feeling he was simultaneously using his forefinger to gauge my pulse?

“… Samuel Montague. I am happy to meet you. Undeniably happy.”

He gave his cap a subservient tip, ending with a two-fingered salute at its brim.

“You have not answered my question, Mr. Montague,” I said. “Do you come here often to observe?”

“The parks of our great city are conducive to reflection,” he said. “I find that a great expanse of grass gives free rein to the mind.”

“Free rein is not always desirable,” I said, “in a mind accustomed to running in its own tram tracks.”

“Excellent!” he exclaimed. “A touch of metaphor. It is a characteristic not always to be found among the Dutch!”

“See here, Mr. Montague,” I said. “I don’t know that I like—”

But already his hand was on my arm.

“No offence, my dear fellow. No offence at all. In any case, I see that your British hedgehog outbristles your Dutch beech marten.”

“What the devil do you mean by that?” I said, leaping to my feet.

“Nothing at all. It was an attempted joke on my part that failed to jell—an impertinence. Please forgive me.”

He seized my sleeve and pulled me down beside him on the bench.

“That fellow over there,” he said in a low voice. “Don’t look at him directly—the one loitering beneath the lime. What do you make of him?”

“He is a doctor,” I replied quickly, eager to shift the focus from myself. The unexpected widening of my acquaintance’s eyes told me that I had scored a lucky hit.

“How can you tell?” he demanded.

“He has the slightly hunched shoulders of a man who has sat by many a sickbed.”

“And?”

“And the tips of his fingers are stained with silver nitrate from the treating of warts.”

Montague laughed.

“How can you be sure he’s not a cigarette smoker and an apothecary?”

“He’s not smoking and apothecaries do not generally carry black bags.”

“Wonderful,” exclaimed Montague. “Add to that the pin of Bart’s Hospital in his lapel, the seal of the Royal College of Surgeons on his keychain, and the unmistakable outline of a stethoscope in his jacket pocket.”

I found myself grinning at him like a Cheshire cat.

I had fallen into the game.

“And the park keeper?”

I sized up the old man, who was picking up scraps of paper and lobbing them with precision into a wheeled refuse bin.

“An old soldier. He limps. He was wounded. His large body is mounted upon spindly legs. Probably spent a great deal of time in a military hospital recovering from his wounds. Not an officer—he doesn’t have the bearing. Infantry, I should say. Served in France.”

Montague bit the corner of his lip and gave me half a wink.

“Splendid!” he said.

“Now then,” he went on, pointing with his chin towards the woman sitting al

one on the park bench closest to the water. “Over there is a person who seems quite ordinary—quite plain. No superabundance of clues to be had. I’ll bet you a shilling you can’t supply me with three solid facts about her.”

As he spoke, the woman leaped to her feet and called out to a child who was knee-deep in the water.

“Heinrich! Come here, my sweet little toad!”

“She is German,” I said.

“Quite so,” said Montague. “And can you venture more? Pray, do go on.”

“She’s German,” I said with finality, hoping to bring to an end this unwanted exercise. “And that’s an end of it.”

“Is it?” he asked, looking at me closely.

I did not condescend to reply.

“Let me see, then, if I may succeed in taking up where you have left off. As you have observed, she is German. We shall begin with that. Next, we shall note that she is married: the rings on the usual finger of the left hand make that quite clear, an opinion which is bolstered by the fact that young Heinrich, who has lost his stick in the water, is the very image of his pretty little mother.

“She is widowed—and very recently, if I am any judge. Her black dress is fresh from Peter Robinson’s Mourning Warehouse. Indeed, the tag is still affixed at the nape of her neck, which tells us, among many other things, that regardless of her apparent poise, she is greatly distracted and no longer has a maid.

“In spite of having overlooked the tag, she possesses excellent eyesight, evinced by the fact that she is able to read the excruciatingly small type of the book which is resting in her lap, and without more than an upward glance, keep an eye upon her child who is now nearly halfway across the basin. What do you suppose would bring such a woman to a public park?”

“Really, Montague,” I said. “You have no right—”

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

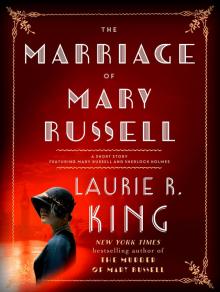

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

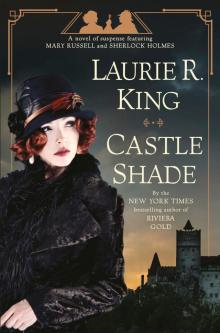

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1