- Home

- Laurie R. King

For the Sake of the Game Page 11

For the Sake of the Game Read online

Page 11

“So this is faculty housing?” DI Hammond asked him.

“This is where the dons reside, yes, sir,” the porter replied stiffly.

“And how many dons would there be in residence at the moment?”

“Well, there’s the master and the dean—they have the ground floor to themselves. One floor up was poor Professor Orville, and Dr. Tanner of the classics department, and Professor Treadwell of modern languages. Up on the second floor there would be Dr. Heathcliff and Dr. Ransom. Both lady dons, you understand.”

“Which is why they’ve been relegated to the top floor?” Clare asked, then realized she should have kept silent. The junior officer does not ask questions unless told to.

The porter gave her a hard stare. “It’s only recently that St. Clement’s has had women on the faculty,” he said. “It was felt they would be happier away from the pipe-smoking males.”

“Quite,” DI Hammond intervened, giving Clare a warning glance.

They followed the porter along a dark hallway, their feet echoing on the tiled floor.

“The dons each have two rooms?” Clare asked, noting names on doors.

“Sitting room and bedroom, next door to each other,” the porter replied. “They share a bathroom at the end of the hall.”

At the far end of the corridor they could hear voices. A door was half open, but most of the light from the doorway was blocked by the chief superintendent’s impressive bulk. He turned at the sound of their footsteps.

“Ah, Hammond. Glad you could make it.”

“Well, it is a death on my patch, sir,” Hammond said easily. Then he added, “Wouldn’t miss it for the world.”

Chief Superintendent Barclay stepped out into the hallway and let them get a glimpse of the room. One young man stood inside the door and Sherlock was moving slowly across the floor, looking more than ever like a rogue vacuum cleaner, skirting around a body that lay sprawled on the carpet.

“As you can see,” Barclay said, “he’s already hard at work. And what’s more he doesn’t want to stop for coffee breaks.” He chuckled at his own joke.

Clare stood back from her DI, trying to take in as much as possible. From where she was standing she couldn’t see a clear cause of death. But she noticed a window was open and the breeze ruffled papers lying on a table. It was an old-fashioned room. On the far wall was a big marble fireplace. Above it hung a hunting print. Apart from the table under the window there were a leather arm chair and a couple of upright chairs. The Spartan room of an unmarried academic, she thought. No photographs, no bright cushions. And no smell of pipe smoke either. But it was also a messy room. Papers and books were piled on every surface. A cup and plate set on the floor beside the chair. A bottle and glass rested on a side table. Professor Orville would have expected the college servant to clear up for him, Clare thought.

“So what do we know so far, sir?” DI Hammond asked. “Before Sherlock tells us whodunit?” He intended it as a joke, but Barclay’s face was serious when he replied.

“Initial examination tells us he was dead for less than an hour when found. Blow to the back of the head. Door locked from the inside. Key still in the lock.”

“Interesting.” Hammond glanced at Clare. He went to take a step into the room but Barclay put out a hand to stop him.

“Well, we’ll leave Sherlock to finish his task, shall we?” he said. “Why don’t you interview the other residents of the building and the cleaning lady?”

Clare could see DI Hammond glowering as they walked away. “Keeping us happy and out of the way. What a farce. I bet that overgrown vacuum cleaner turns up nothing useful.”

They were taken down the hall to a small kitchen where Ada, the college servant, was sitting, being consoled by a young policewoman. She glanced up and smiled as DI Hammond entered. “Oh, hello sir. This is Ada Johnson. She was the one who found the body.”

“Hello, Ada,” DI Hammond said kindly. “Bit of a shock, eh?”

“Oh yes sir,” Ada turned a mournful face to him. She had been crying. “He was a lovely gentleman. Ever so kind. Of course, he wasn’t the tidiest of gentlemen. Especially not when he was working on something. Your typical absentminded professor, so to speak.” She smiled wistfully. “Always spilling things on the rug. But at least he didn’t smoke so he didn’t burn any holes, like some of them.”

“So tell us exactly what happened this morning,” DI Hammond said.

“I went to clean his room as usual about nine o’clock,” Ada said. “I always start with him, seeing he’s got the end rooms. I made his bed as usual, and then I tried his sitting room and it was locked. That surprised me because I know he teaches a nine o’clock class on Tuesdays. He always leaves the key in the lock so I can go in and clean for him. I wondered if he’d been working late and fallen asleep in his chair.” She looked up at them. “He’s done it before, you know. And he likes his whiskey on occasion.”

“So what did you do?”

“I knocked, sir. I banged on the door. Professor Treadwell came out to see what the commotion was about. I told him and he went to get the porter with the pass key. We opened the door and there was the poor professor lying there, dead as a doornail, sir. It quite took me funny. And the professor went and phoned for the police.”

“When did you last see the professor alive?”

“Well, sir, I didn’t see him yesterday when I went to clean his room, but I heard him.”

“Heard him?” DI Hammond asked.

“Yes, sir. He wasn’t in his rooms when I came. I made his bed and then I went through to his sitting room and I was sweeping the floor when I heard a right old barney going on upstairs. Dr. Heathcliff’s rooms are directly upstairs from his and the sound echoed down the chimney. They were going at each other. She called him a pedantic old bore who was past it and should step down, and he called her a meddling and ambitious harpy who wasn’t above stealing someone else’s research.” Ada paused and looked up at them. “I left them at it, sir, and went on with my cleaning. These scholarly folks, they do get quite het up about their work sometimes.”

“Has Professor Orville argued with any other colleagues lately?” DI Hammond asked.

“Not that I’ve overheard, sir. He gets on well with everybody most of the time. He’s especially thick with Professor Treadwell and with the master.”

“And what about outside visitors?”

“I believe his sister comes to visit him sometimes, and of course students come up to his rooms on a regular basis. Any outsider would have to go past the porter’s desk and sign in.”

DI Hammond turned to Clare. “Any questions you’d like to ask, Constable?”

“Yes,” Clare said. “Did he often keep his door locked?”

“Not usually in the mornings, because he knew I’d want to get in to clean for him, but I imagine he did lock himself in when he wanted some privacy. They don’t just want undergrads barging in on them, do they?”

“And who might have access to the pass key besides the porter?” DI Hammond asked.

“Oh nobody, sir. The porter guards that key with his life.”

“Besides,” Clare pointed out, “if the door was locked from the inside then the key would have been in the lock, wouldn’t it? When the porter pushed his pass key in, the inside key would have fallen to the floor.”

“Quite right,” DI Hammond nodded approvingly. “Thank you, Ada. You’ve been very helpful. Now if we might have a word with Dr. Heathcliff, if she’s available?”

“She should be in her rooms still,” Ada said. “She doesn’t teach until a tutorial at noon. Up the stairs to the rooms at the far end.”

Clare fell into step beside DI Hammond. “What do you think, sir?”

“Since we haven’t been able to view the body, I have no idea,” he replied. “The door locked from the inside? Someone’s been quite clever.”

They went up a second stone staircase and tapped on the end door of an upstairs hallway, if anything more gloomy

than the first.

“Enter,” boomed an authoritative voice. They entered a very different room. This one was clearly a woman’s room. The walls were lined with bookcases and there were neat stacks of papers on a desk against the far wall. But the window seat was piled high with pillows and there were embroidered pillows on a chintz-covered sofa. On the coffee table there was a dish containing Murano glass beads and a half-finished necklace beside it. And plants—lots of plants everywhere. Clare detected the faint smell of smoke in the room and wondered if the plants were an attempt to cover up the woman’s smoking. There was a slight movement and Clare noticed a large white cat asleep amongst the pillows.

“Miss Heathcliff?” DI Hammond asked pleasantly.

“It’s Doctor Heathcliff,” she said curtly. The woman came toward them. She was large but not fat—a draught horse, not a thoroughbred. If she had been wearing a suit she would have come across as a formidable presence, but she was wearing a loose, flowing dress and an intricate beaded necklace. Clare wondered if this was a deliberate attempt to soften a dominant personality. She was interestingly complex—the orderly shelves of books and papers and the hand-embroidered pillows and folksy attire showed two very different sides of the same woman.

“I beg your pardon, Doctor,” the DI said. “I’m DI Hammond and this is Constable Patterson. I wonder if we might have a few words.”

“About Professor Orville, I presume?”

“You’ve heard?”

“Of course. And I’m very sorry. We didn’t always see eye to eye but he was a good man. An intelligent man. Was it a burglary? I wouldn’t have thought he had much worth stealing.”

“We haven’t had a chance to view the crime scene yet,” DI Hammond said. “But we wanted speak to potential witnesses first.”

“I’m afraid I can’t help you. I haven’t seen him since yesterday morning,” she said.

“When you apparently had an argument,” DI Hammond said evenly.

“We did.”

“Would you mind telling me what it was about?”

“Bacon,” she said.

“One of you is a vegetarian?”

She gave a rather patronizing laugh. “I’m talking of Francis Bacon. I am writing a paper on new evidence proving he wrote some of Shakespeare’s plays. Orville disagreed strongly. He urged me to drop it.” She looked up sharply. “You can’t possibly think I had anything to do with his death. You don’t kill somebody because you disagree academically.”

“Of course not,” the DI responded. “But would you like to tell us what your movements were this morning?”

“This morning? Is that when he was killed?” She shook her head in disbelief. “I heard nothing.”

“You were in your room all the time?”

“No. I always go for my walk at eight o’clock. The same every morning. I cross the meadows to the Cherwell, go along the river and back through Magdalen. If you want to check on my movements I always pass the same people: a couple with a small white poodle; Professor Tweedie from Brasenose; and I generally exchange pleasantries with the porter at Magdalen. I return home between eight forty-five and nine. I have been in my room since then preparing for a tutorial.”

“Can you think of anyone who would want to harm Professor Orville?” DI Hammond asked.

“He could be infuriating at times,” she said. “Completely disorganized. That room of his. . . . Hopeless. I gave him one of my plants, but I suspect he’s let it die by now. But hating him enough to kill him? One of the students went off his rocker, I suppose. They do, sometimes. It’s the pressure of exams.”

“I wouldn’t like to get on the wrong side of her,” DI Hammond muttered as they left Dr. Heathcliff’s room.

They proceeded to interview those members of the faculty who were still in their rooms. None had seen Professor Orville that morning nor heard any sign of a fight. They returned to Barclay.

“Well?” Barclay asked. “Anything suspicious?”

“Only that the female don upstairs had an argument with Orville yesterday. But she is out on her walk between eight and nine and you suggest the time of death was around eight thirty?”

Barclay nodded.

“And besides,” Hammond went on. “She’s a rather large lady. She wouldn’t fit through Orville’s windows and I doubt she could climb down the wall.”

“Sherlock’s done with the floor and now he’s collecting fingerprints,” Barclay said. “In an hour or so we should know something. I suggest you keep yourself busy by getting fingerprints from the occupants of this building.”

“Good idea. Why don’t you do that, Constable Patterson?” DI Hammond said.

Clare nodded and went to collect a fingerprint kit.

“You again,” Dr. Heathcliff said, frowning, as Clare returned. “Fingerprints? Of course they’ll find our fingerprints all over his room. We met for sherry every Friday evening. Is there anyone competent handling this investigation?”

“A robot,” Clare answered.

“There is no need to be facetious with me,” Dr. Heathcliff snapped. “Now, if you will excuse me, I have a tutorial.”

Clare handed in her fingerprints and then she went with DI Hammond to break the news to Orville’s sister, who lived in a terrace house on the other side of Folly Bridge over the Isis. She was a tiny sparrow of a woman and she looked up at them fearfully as DI Hammond broke the news.

“I was worried when he didn’t telephone me this morning,” she said. “He always did, at eight o’clock on the dot. Was it his heart?”

“We’re not sure yet,” DI Hammond said. “May we come in?”

She offered them tea and seated them in a tiny sitting room. A calico cat rubbed up against their legs.

“So tell me about your brother,” DI Hammond said.

“I did my best to look after him,” Miss Hammond said. “He was hopeless. He’d never have changed his clothes or washed his shirts if I hadn’t made him. Head up in the clouds. Always, even as a boy.”

“When did you last see him?”

“He came to me for Sunday lunch regularly. And sometimes he’d come over and we’d play Scrabble. But Sunday, that was the last time.” She put a hand to her mouth as if she’d just realized what she had said. “The last time,” she repeated.

“Was your brother worried about anything? Did he have any enemies?”

“Enemies?” She shook her head. “He was the most gentle of creatures. Easygoing. Mild-mannered. Content with life.”

They left soon after and returned expectantly to St Clement’s. As they entered they heard a booming voice coming from the upstairs hallway. “Don’t be so ridiculous! Keep your hands off me!”

Barclay appeared. “All sewn up while you were away, Inspector. It was the woman upstairs. The one he was arguing with. She couldn’t stand him.”

“Dr. Heathcliff? How could you tell?”

“It was Sherlock who told,” Barclay said with his self-satisfied smile. “The carpet had been cleaned yesterday morning so anything found on it was fresh. And what was found were the following: damp soil. A blade of grass . . . and we know that woman crossed the meadow on her walk—which she clearly took earlier than usual today. A white cat hair and we know she has a white cat. And a spent match . . . she smokes, he doesn’t. And the phone was hanging down from its cord. He went for the phone and she struck him from behind. Maybe on impulse. Maybe she didn’t mean to kill him.”

“But the locked door?” Clare asked.

“Clever.” Barclay nodded. “The woman is into craft work. She does beading and has a pair of long-nosed pliers wrapped in silk cord to prevent her from damaging expensive beads. She put them through the keyhole and turned the key from the other side, leaving no marks on the key. Brilliant.”

“And do we know how he was killed?”

Barclay was still smiling. “That fireplace surround. Those marble balls come off the fender. She hit him with it and then replaced it, wiping off her fingerprints. But there

are still traces of blood and hair.”

He went to walk away.

“Do you mind if we take a look now Sherlock is finished?” DI Hammond asked.

Barclay shrugged. “Please yourselves. They are coming for the body soon.”

He went out, closing the door behind him.

“Well that’s nice and neat, isn’t it?” Hammond turned to Clare. “Do you think she did it?”

“I suppose it does all make sense,” Clare said. “You said she was a woman you wouldn’t want to cross.”

DI Hammond knelt to examine the body. There was an ugly wound on the side of the head. Clare looked around the room. The marble ball on the fireplace fender still had clear traces of blood and hair on it. Why not wipe it clean if you had wiped off fingerprints? And on the windowsill was the plant Dr. Heathcliff had given him. Indeed in a sorry state, but it had been watered recently. He must have been trying to revive it. She glanced into the fireplace. The weather had been warm so there was no fire, but there were a few ashes.

“I think he burned something recently,” she said. “That would account for the match on the floor.”

DI Hammond stood up.

A breeze came in through the window and ruffled the papers on the sill. Clare stood there, frowning. If that breeze had been stronger it would have knocked over the plant, and soil would have spilled onto the floor. And the lawn in the quad was being mown. A blade of grass could have easily blown in through the window. And the white cat hair? He had visited his sister with the calico cat and he never brushed his clothing. . . .

Then she looked down at the body and a big smile spread across her face. “I don’t think it was a murder at all, sir,” she said. “It was an accident.”

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

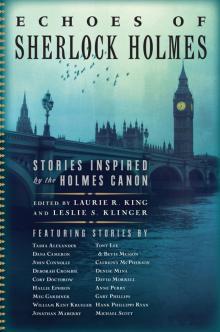

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1