- Home

- Laurie R. King

A Grave Talent km-1 Page 13

A Grave Talent km-1 Read online

Page 13

"They're not that bad." She just wanted to sleep, for a week.

"No, I suppose you could go on leaking all over everything until you collapsed, if you like."

"It's just a gash," she protested.

"I mean the ones on your back, or hadn't you noticed that there's blood clear down your leg?"

Kate reached back with her hand, and drew it back red. She felt suddenly weak.

"No, I hadn't. It must've been from the window. Can't you do something? Just put a butterfly bandage on it or something?"

"That really should be seen by a doctor," the nurse hedged, in a tone of voice that said she often had done things of the sort without a doctor's supervision.

"I sure as hell am not going to report you to the AMA, and these two are too busy to notice. Just do something to keep it from getting any worse."

She allowed Terry to push her onto a stool, where she sat, vaguely aware of a male voice ordering the room cleared, of Terry preparing a hypodermic with novocaine, of scissors on cloth and the needle prick and spreading patches of numbness on her back, of the sure hands and the tug of stitches. All the time, though, she was fully aware only of the body on the floor, the pale chest with its small breasts and blue veins beneath the strong dark hands of the medical technicians who fought hard, impersonally, for her life. At one point she heard a distant voice that she realized had been hers.

"You're working on another Cezanne," she told them, "a female Renoir." The less occupied of the pair glanced up at her curiously. "That's Eva Vaughn."

It obviously meant nothing to him, but the other one glanced up, startled, to meet her eyes for an instant. The wide mouth remained slack, the eyes stayed rolled up under the pale lids. Behind her Terry stitched and clipped and bandaged, and disappeared for a few minutes before returning with a soft flannel shirt, slightly too long in the sleeves. She fumbled with the unfamiliar apparatus of the shoulder holster, and eased it off Kate along with the shreds of her shirt, then gently dressed Kate again. Kate never took her eyes off of Vaun.

The hand that had painted Strawberry Fields lay forgotten on the floor like a crushed flower. Kate sat and stared at the slightly curled fingers, the short fingernail edged with blue paint, and knew that she had not been fast enough. When one of the men sat back on his heels, she closed her eyes at the words to come.

"We have a heartbeat."

It took a second to sink home. Kate's eyes flared open to see the man's expression, of faint hope and satisfaction.

"She's not—she'll make it?"

"Her heart's beating. There's no telling yet what damage there's been, or when she'll breathe, but the heart's going. Let's get her on the stretcher," he said to his partner, and to Kate, "You'd better come too, you're not looking too hot."

"No."

"Casey, you need to see a doctor," Terry protested.

"No. I'm staying here until I'm relieved."

"Your choice." The paramedic shrugged. "She'll be at the General in town." He secured a blanket and the straps around Vaun. She looked white now, not blue. Terry fretted around Kate until the man suggested that if she would carry some equipment it would save them a trip back up. Kate followed them to the door and stood watching the men navigate their burden down the hillside to the helicopter, whose spotlights overcame the dim remains of the bonfires. She closed Vaun's front door and turned the key. How long would it be before the anesthetic wore off? she wondered. Better take a look at the place now, while I can still move.

Kate walked like an automaton through each of the downstairs rooms, checking windows, comparing the rooms with what she had seen the day before. Upstairs the studio looked much as it had, tidy, on hold but for the two brooding easels. The slab of glass that the artist used as a palette had moved and grown a smear of brilliant orange-red, and there was a large, white-bristled brush she didn't remember seeing. The figure on the undraped canvas had evolved into a woman, unidentifiable as yet. The spiral-bound drawing pad which Hawkin had left on the top of the cabinet under the south window was now on the long table. When Kate lifted the cover, the only drawing was the quick charcoal sketch of her and Hawkin coming up the hill, the tall trees still seeming to flinch away from the ominous challenge of Hawkin's gaze. She touched it lightly, and found that it had been sprayed with fixative. In the spiral binding there was an edge of perforated paper behind the drawing. Vaun had done at least one other, and torn it out—or, she corrected herself, it had been torn out. No point in looking in the fireplace for it now. She straightened, wincing, and went to check the studio windows, which had sliding metal frames. Each one was firmly caught in its latch until the second to last one next to the storage room, which flew open unexpectedly at her tug and caused her to curse with the awakened pain from a hundred sites down her back and legs and arm and—. She stood still for a long moment until the worst of it had passed, then let out her breath in a hiss and turned back to the window. She wished for her flashlight as she examined the frame and the track, slid the window shut again, pulled at it tentatively. It had latched. She looked more closely at the windowsill and picked up a tiny sliver that lay there, pursed her lips in thought, put it back down where she had found it, and went downstairs to the walkie-talkie. She swore again as she tried to bend down to where it had been kicked, just under the edge of the sofa, but gave that motion up quickly and settled for a sort of sit-and-slump to the floor. The casing looked a bit squashed; she wondered if it still worked.

"Al? Anyone home?"

"Hawkin here."

"They're taking her now. They managed to get her heart started again."

"Thank God. Are you going with them?"

"No, I'm staying here."

"Tommy Chesler was down at the washout a few minutes ago. He said you'd been hurt."

"Scrapes and cuts, that's all."

"Go with the helicopter, Casey, somebody should stay with her."

The shots were definitely wearing off, and a wave of weakness and pain and heavy exhaustion washed over her.

"Oh, Christ, Al, she's not about to take off on us, not for a long time. Damn it, she may be a vegetable the rest of her life."

"I want you out of there."

"No."

"Why the hell not, Martinelli?"

His anger sparked her own, and the truth tumbled out of her.

"I don't know why not, Al. I have a bad feeling about this, but I hurt and I've lost some blood and I know my brain isn't functioning properly. I can't think straight, but there's something here that smells rotten, and if I stay here I'll be able to see it more clearly in the morning. It's too late to argue, Al, they've already left, and I'm going to sleep for a few hours. And if you call me on this damn thing before seven tomorrow morning I will not be held responsible for your eardrums."

It was very comfortable, leaning against the sofa in front of the fire, but the upholstery and the carpet were spattered with her own blood and stank sourly of vomit and Kate couldn't bear to think of sleeping there, or on Vaun's bed for that matter. She walked across the carpet on her knees to load a few logs into the stove, crawled upright against the armchair, and stumbled upstairs again. The studio sofa was so stained and battered already, a bit of blood and dirt would pass unnoticed. She eased herself down face first, with the walkie-talkie and the probably useless gun close at hand, and fell gratefully into darkness.

The crunch of shoes on glass brought her awake some hours later. She reached for her gun, but the sudden movement of her back muscles lit the flames of the two deep cuts and the thirty-odd needle punctures from the stitches, to say nothing of the bruises. She must have made a noise, because the feet stopped.

"Casey?"

"Al? Is that you? I'm upstairs."

It was ridiculous, but without adrenaline she could only inch off the couch like an old rheumatic cripple. The anesthetic had most emphatically worn off, and the burn of the glass cuts added to the torn thigh, gouged arm, scraped hip, and several square feet of bruises made her stand very

still and wish she could get by with just moving her eyes.

Even in the dim lamplight she must have been a sight. Hawkin stopped abruptly.

"God in heaven, what happened to you?"

"Just a nice hike in the woods, Al. Hey, don't look like that. It's mostly mud and bruises. They'll scare children for a few days but won't bother me by tomorrow. Really. I'm just stiff."

"Nearly a stiff, by the looks of it. Let me see your back."

"Al, I'm fine."

"That's an order, Martinelli."

She started to shrug, thought better of it, and turned to let the dim lamp shine on her back. He lifted the long tail of Vaun's shirt, peeled back the tape, looked and gently touched one or two spots, and let it fall.

"No internal bleeding? No ribs gone?"

"None. I wouldn't even have the cuts if I had taken more care with the window."

"You were in a hurry."

"I was. Any news of her?"

"The same."

"How did you get here?"

"Helicopter."

"I didn't—" She stopped. "I guess I did hear it, but I thought I was dreaming. You could have left it until morning."

"And if the wind comes up again? You'd be here for days. Show me what made you want to stick around."

"A lot of little things. No note, though of course not all suicides leave one. No pills—whatever she took was dissolved. The whiskey bottle looks like it was wiped clean. There's about an inch in the bottom for the lab to check. She also set the table for dinner and had a pot of some kind of stew on top of the stove, which got pretty scorched before Terry Allen pulled it off. The book she was reading did not strike me as the sort of thing I personally would want to have as my last conscious awareness, while it would be ideal as a way of taking the mind off an unpleasant day. Light and undemanding. Her painting's not finished, but she worked on it during the day. Then there was this, in the only window that was not securely latched, though it was closed."

Hawkin picked up the sliver of wood and took it to the light.

"Shaped with a knife," he commented.

"It looked like it."

He turned the sliver around thoughtfully between thumb and fingers, and studied her face. She was obviously fighting a losing battle to keep fatigue and pain at bay, but there remained a stubborn set to her mouth and defiance in her eyes. She was tough, this one.

"You don't want to think she's guilty, do you, Casey?"

"What I want has very little to do with it at this point," she said stiffly.

"I wouldn't say that."

"Al—"

"But you're right, of course. It does smell wrong." He turned away, ignoring the astonished relief that flooded into her face, and spoke into the walkie-talkie.

"Trujillo?"

"Trujillo here."

"I'll be leaving your man here tonight, if you'll tell his wife. Also, I need you to get through to my people and tell them I want Thompson and his crew down here first thing tomorrow, and that it has to be Thompson. I'll be leaving here in a little while with Casey. I'll see you at the hospital in the morning. Got that?"

"All clear. How's Casey?"

"She looks like hell and no doubt feels worse, but she'll live. Hawkin out."

Hawkin retrieved Kate's equipment and found a wool blanket in Vaun's bedroom to wrap around her shoulders. They left the warmly dressed sheriff's deputy on guard and walked slowly down toward the glare of lights in back of the Dodson house. Movement helped sore muscles not to stiffen, Kate told herself fiercely, a number of times.

"Several questions come to mind, do they not?" Hawkin mused. "If this is not a suicide attempt, and I think we can safely rule out accident, who would want her dead, and why?"

"Someone here, on the Road."

"Who knew her habit of a drink before dinner, assuming the lab finds something in the bottle, and who had access to the bottle since last night. I suppose he planned on planting a suicide note and clearing up anomalies like the pot on the stove when he came back. Or she. Or maybe he just wanted to make sure it worked. Maybe he realized that a drug is an uncertain means of killing someone."

"It must be related to the other murders."

"Two unrelated murderers in one small area is unlikely, I agree. Revenge? Fear? Or somebody who knew the woman's past decided to use it to explain her suicide, just taking advantage of an unrelated situation, like he took advantage of the storm, which would have delayed anyone finding her until it was far too late, had it not been for a stubborn policewoman. Woman murderer commits remorseful suicide, case closed."

"And if the killings didn't stop?" It was hard to think against the jolting pain of walking on uneven ground, but Kate tried.

"Ah, there's the prize question, which leads us into a very… interesting possibility. A whole different ball game." His voice was distant, but when Kate stumbled on the rough track in the bobbing flashlight beam, his free hand was there on her elbow, steadying her.

"You sure you're okay walking? I can get a stretcher."

"No, I'm fine, just tired."

"You realize, of course," he continued as if the interruption had not occurred, "that one possibility, a small one, I admit, but worthy of consideration, is that Vaun Adams has been the target of all this, that those three little girls gave their lives to set her up for suicide."

"Oh, come on, Al, that's…"

"Farfetched? Yes. The work of a madman? That too."

Kate began to shiver. "But why? Why would someone hate her so much? Why not just bang her over the head on one of her walks and make it look like an accident?"

"You find who, I'll tell you why. Or vice versa. I agree it's a crazy idea, but it does fit better than the theory of Vaun Adams as a psychopath wanting to be caught."

They had come up to the Dodson cabin now, the helicopter just beyond. Eight or nine residents stood in an uncertain group near a pile of brush and wood.

"Good evening, Angie," Hawkin greeted her, "and Miss Amy. Thank you for your help this evening."

"Is Vaun going to be all right?"

"I don't know. If anything comes through I'll send word by Trujillo. I'm glad your husband made it back before the road went out. Is he here?"

"He and Tommy went up the Road to let people know what's happening. Everyone will have heard the helicopters."

"Right. Look, Angie, tell him to go down to the washout tomorrow and give someone his statement. If the wind stays down we'll be around here, but he and old Peterson and a couple of others are missing from the records."

"I'll tell him."

"Thanks. 'Night, everyone, you can let the fires go out. Maybe you should leave Matilda in her stall tonight, though. We'd hate to land on her head in the morning."

The cold and the pain and the loss of blood had Kate trembling by the time they reached the copter, and Hawkin and one of the paramedics had to help her climb in. The man wrapped her in more blankets, strapped her in with Hawkin at her side, closed the door, took his own seat. She had seen his face before. Why was thinking becoming so laborious? His face, bent over Vaun's still body with the mask. What was wrong there, what was so terribly stupid? The copter lifted off, Hawkin leaned into her, and she knew what it was.

"Al, these two paramedics? They know. Who she is, I mean. I said something to them—"

"It's all right. They told me what happened, and I had a talk with them. They understand, and they won't blab. You done good, kid. Have a rest now."

Her body hurt all over, but in her mind the words brought relief, sweet relief. She leaned against Hawkin's broad shoulder and surrendered to the darkness.

TWO

THE PAST

Contents - Prev/Next

The past is but the beginning of a beginning.

—H. G. Wells, The Discovery of the Future

It was all so long ago, so closely encompassed and complete;

so cut off as by swords from the bitter years that lay between…

And afterwards, the s

tark shadow of the gallows

had fallen between her and that sun-drenched quadrangle of grey and green.

But now—?

—Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night

14

Contents - Prev/Next

California spent the weekend at the task, familiar to her assorted generations, of digging herself out from under mounds of debris and rubble. The whine of chain saws filled the air; the scrape and slop of shovels moving mud, the taps and bangs of hammers replacing shingles and panes of glass were heard in every corner. There was a belated run on candles and purified water, "for next time." The repair trucks from the gas and electric company and the telephone companies and the cable television companies pushed gradually farther out from the centers into the hills, and deep-freezes hummed back to life, telephones rang, televisions brought pictures of the other storm victims. Power at Tyler's Barn was reestablished on Monday, and the first thing Tyler's lady Anna did was to put Vivaldi's Gloria on the stereo and blast the joyous chorus up into the hills, startling the pale horses. She found the house exceedingly dreary without lights and refrigeration, and had it not been for all the extra residents who needed feeding she would have escaped the close surveillance and the noise and tension with all the others who were now visiting friends and family.

The Sunday papers all ran full-page photographic spreads of the storm, freak incidents and bizarre incongruities next to close-ups of mud-smeared faces caught in attitudes of fear or exhaustion or agonized relief. The events on Tyler's Road rated a small paragraph, and Kate wondered how long it would be before some enterprising reporter discovered that the unconscious woman being treated for a drug overdose was also an artist whose last show had brought well over a million dollars in sales.

Tyler's Road reemerged in its entirety over the next few days, as Tyler, with Hawkin glaring over his shoulder, arranged for an unprecedented amount of huge machinery to invade the bucolic hills and lay two larger culvert pipes and scrape the mudslide from the Road's upper end. Kate spent two days lying uncomfortably on her side, reading a ridiculously thick stack of files and trying to urge her back and leg to heal. Al Hawkin spent sixteen hours a day on the case—up at Vaun's house, meeting with the representatives of three counties, the FBI, and the press, talking to three sets of parents, staring out of various windows—and began to show it.

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

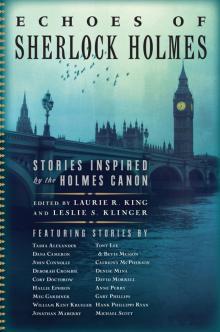

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1