- Home

- Laurie R. King

The Game Page 27

The Game Read online

Page 27

“Walk? That must have taken days—what was Bindra’s reaction to that?”

“He was not pleased. I did offer to provide him with a ticket back to Kalka, but for some reason the boy decided he would rather stay with me. So we walked, and caught rides on bullock-carts and tongas, and stopped regularly to thaw ourselves out in wayside hostelries, drinking tea with the locals and gossiping about this and that.”

“Monks, particularly,” I suggested.

“By all means, especially considering the way a certain scoundrel of a red-hat Buddhist monk had just made off with my purse and train ticket, leaving me to trudge through the snow and survive on cups of tea bought with the few coins that remained in my pocket.”

“And did any of them recall another such monk, oh, say about three years before?”

“Surprisingly few. And both of those who did—the sweeper of one inn and the cook in another—remembered him as going uphill, towards Simla, not away.”

“So he took the train out,” I said, disappointed.

“Or went overland to the north. In the summer months, the passes there would be reasonable, for a man who loves the hills at any rate. One thing did come to light: A band of dacoits—robbers—was working in the area north of Simla during that time.”

“Do you think—?”

“I think it highly unlikely that Kimball O’Hara was the victim of casual dacoitry.”

Still, it gave me thought, as I walked along. A while later, another question came to mind.

“What did Bindra make of your tale of woe?” I asked.

“The boy seemed unsurprised. In fact, he tended to embellish my stories rather more than was necessary.”

And that, too, was thought-provoking. The child was shrewder than he appeared and without doubt unscrupulous, but I could not bring myself to picture him as a spy planted in our midst, by Nesbit or anyone else. For one thing, the child was too young for that sort of sustained purpose of mind: Holmes had habitually used youthful Irregulars in his Baker Street days, but only for specific and limited missions.

But if the child was not there under orders, why did he stay? And more to the point, why did he not question the oddities of Holmes’ behaviour?

The mysteries kept me occupied all that day, but they remained mysteries.

We set up that night in a village of perhaps ninety souls, earning a handful of copper for our pains, but with the coins supplemented by a generosity of food and fodder. The village got a bargain, because in my absence Holmes had cobbled together the equipment for a new act which, together with the levitation frame, my bottomless Moslem cap, and the conversions to the blue cart effected by blacksmith and carpenter back in Kalka, was spectacular enough to make even the least superstitious folk uneasy.

Not until we were in our bed-rolls that night could we speak freely, murmuring into each other’s ears in English, the sound inaudible from outside the walls of the tent. Holmes had been thinking about what I had said.

“You say Old Fort appears deserted, but is not,” he said.

“There are no lights, but when one watches with care, one sees the occasional splash of lamp and gleam of a sentry’s gun atop the walls. And twice, a guard’s careless cigarette.”

“What of its gates?”

“They are generally open. I presume they’re guarded, although if the men are anything like those on the main gates, it should be no great task to get past them. You wish to see inside Old Fort?”

“Why else should we be here?” he asked.

Why else, indeed? “I merely thought that perhaps we ought to send word to Nesbit first, in case something happens.”

“Report or no, Nesbit knows where we are. Our disappearance alone would tell him all he need know.”

Slim comfort.

We moved on the next day, our path a wide circle leading back to The Forts. Here the ground was less fertile, with fewer people working the fields. We strolled the dusty road, the unnaturally amiable donkey following along behind, and as we went I tried to describe the maharaja and his coterie.

“He is, as Nesbit said, a fine sportsman. Having ridden after pig myself now, I understand Nesbit’s praise of the man. Of course, he’s completely insensible to damage inflicted on horses or coolies, but he does play the game by the rules, and was unwilling to leave a wounded boar to die in the bushes.”

“Which may merely be because, were the boar to recover, it would be both ill tempered and experienced when it came to men.”

“True, and it wouldn’t do to have a berserker pig come after, say, a visiting Prince of Wales.”

“But you already told me that the hearty sportsman is not the only side to his personality.”

“His cousin said it: He collects grotesques. In his zoo, but also the people living under his—ach, the sun is so hot today,” I broke off to say, as a farmer reclining in the shade of a tree stirred and sat up at our approach. Holmes asked the man about the next village, and learned that it was tiny but that a few miles farther on was a larger village, with two wells and many clay-brick houses. We thanked him, shared a bidi with him, and returned to the road.

“You were saying, Russell?”

“His pet grotesques. He collects them, but I would have to say, he also creates them. In the zoo, he plays God with animals, seeing how far he can drive them before they go mad. And in the palace, he does a similar thing with his ‘guests,’ finding their weaknesses and twisting his blade in an inch at a time. It’s a game to him, baiting and teasing his hangers-on, undermining their skills, seeing if he can drive them nuts.” Then I told him about the zoo, the casual extermination of the thin creature and my impression that he was using the act deliberately to disturb Sunny Goodheart. And, for the sake of completeness but feeling somewhat embarrassed, I went on to describe the toy room, its taxidermied inhabitants, and my profound distaste for that as well.

Holmes walked for a while, staring sightless at the bright wagon, deep in thought. I was braced for his disapproval, that I had not told him this part of it earlier, when I first saw him in Khanpur city. I had my refutations all in a line: that simply failing to reappear in The Forts would have stirred up all kinds of uproar, that not being a small furry animal nor a servant, I was hardly in any danger, and so on. But he just kept walking, and eventually sighed to himself, as if he’d gone through all my arguments in his head and had to admit my position. Sometimes, the speed of Holmes’ wit could be disconcerting.

“An unbalanced man” was, in the end, all he said.

“But you, Holmes, you’ve been in Khanpur nearly as long as I have. What impression of the prince have you got from his subjects?”

“The people are extremely wary of their ruler. They acknowledge that he has improved their lot in any number of ways, appreciate that their sons are learning to read and that their villages have clean water, but they accept these things with the caution that an experienced fox will use in retrieving bait from a trap. And twice I have heard rumours of men vanished into the night.”

“Men, not women?”

“Strong, middle-aged men.”

“Not the sort of target one would expect for perversions.”

“No. And as evidence, it would be dismissed by the most forgiving of judges. Men disappear for any number of reasons, in Khanpur as in London.

“So tell me, Russell, having spent five days in his company: If the maharaja of Khanpur did lay hands on Kimball O’Hara three years ago, would he have killed him or kept him?”

“Kept him,” I answered instantly, then thought about it. “Assuming he knew who the man was. And unless O’Hara drove him to murder.”

“For what purpose?”

What Holmes was asking me to do might to the uninitiated sound like guesswork, but was in fact a form of reasoning that extended the path of known data into the regions of the unknown. Unfortunately, this sort of reasoning worked best with the motivations and goals of career criminals and other simple people; the maharaja of Khanpur was n

ot a simple man.

“I can envision two reasons, although they would not be exclusive. One is, for lack of a better term, political: The maharaja knows O’Hara is in fact a spy, and he wishes to extract from him all possible information about the workings of the British Intelligence system. Although after three years, I can’t imagine there would be much he had not got out of the man.”

“You see political power as the maharaja’s goal?”

I found myself fiddling with the silver-and-enamel charm around my neck. “Nesbit indicated something of the sort, that a native prince might be a compromise between the Congress Party and the Moslem League.”

“Even if he does not come into power through the ballot box.”

“You think the maharaja is setting up a revolution of his own? He could hardly expect to take over the country as a whole.”

“Even a small blow at the right place might be enough to shatter the British hold on the country, given the current political climate.”

“ ‘By surprise, where it hurts,’ ” I murmured. Goodheart’s drunken cry at the costume ball had stayed with me.

“Precisely. And the provocative elements in this drama are mounting.”

“His friendship with a self-avowed Communist who, according to his sister, has considerable experience with aeroplanes—perhaps to the extent of piloting them himself,” I said. “The capture—possible capture,” I corrected myself before he could, “—of one of the lead spies of the occupying power.”

“His superior air field, with stockpiled arms and explosives,” Holmes added. “Its proximity to the border. A trip to Moscow; three British spies found dead in the vicinity of Khanpur.”

“The remarkable number and variety of guests who come through this rather remote kingdom.”

“The maharaja of Khanpur as a Lenin of the sub-continent?” Holmes mused. “We are reasoning in advance of our data, but it is an hypothesis worthy of consideration. What was your other reason?”

“My other—? Oh yes, for keeping O’Hara in custody. Because the maharaja wants to gloat over him. Not openly, but secretly—what was it he said to me? ‘I like to keep some things to myself.’ His private rooms show it, that the things that are really important to him he guards close to his chest. And,” I said more slowly, trying to envision the complete picture, “maybe he even regards it as a sport, trying to get inside the man and twist him.”

Holmes did not respond, and I glanced to see his reaction. His face was stoney, his eyes far away.

“Holmes, I’ve heard a great deal about Kimball O’Hara, from you and from Nesbit, and I suppose you could say from Kipling’s story before that. So, what is O’Hara’s weakness? How would the maharaja turn him?”

We had covered half a mile before Holmes answered me. “O’Hara’s greatest weakness, when I knew him, was his unwillingness to lie. Oh, he was superb at playing The Game, turning the truth until it went outside-in, creating stories for himself—those small deceits of history and character that are part of a good disguise. But when it came to direct questions, and particularly when dealing with a person who knew him, telling a lie was almost physically painful for the lad. He had an almost superstitious aversion to breaking his word.”

I thought about this the remainder of the afternoon, asking myself how a person might use a man’s honesty against him. Offhand, I couldn’t come up with anything terribly likely, but I had no doubt that, if it were possible, the maharaja of Khanpur would be the man to do it.

Well before dusk we came to the village the farmer had described to us, a small but prosperous collection of walls and trees, fields stretching out in all directions. I waited with the donkey and cart, surrounded by the excited twitter of the village children, while Holmes came to an agreement with the headman. We set up camp beneath the assigned tree, then hobbled the donkey and gave it food.

Dusk settled in; the men came in from their labours; the odours of dung fire and spices rose up in the soft air. I missed Bindra, more than I would have thought, and hoped the urchin had found safe haven on the other side of the border—and then I caught myself and chuckled aloud. That boy would survive in a pit of angry cobras.

The sky shed the sun’s light, giving way to half a moon, and Holmes and I readied ourselves for the evening performance.

It was a dramatic setting for a human sacrifice, give my murderer credit. He had drawn together the entire populace, crones to infants, in a dusty space between buildings that in England would be the village green, and all were agog at the sight. A circle of freshly lit torches cracked and flared in the slight evening breeze, their dashing light rendering the mud houses in stark contrast of pale wall and blackest shadow. The bowl of the sky I was forced to gaze up at was moonless, the stars—far, far from the electrical intrusions of civilisation—pinpricks in the velvet expanse. The evening air was rich with odours—the oily reek of the rag torches in counterpoint to the dusky cow-dung cook-fires and the curry and garlic that permeated the audience, along with the not unpleasant smell of unsoaped bodies and the savour of dust which had been dampened for the show.

I lay, bound with chains, on what could only be called an altar, waist-height to the man who held the gleaming knife. My sacrifice was to be the climax of the evening’s events, and he had worked the crowd into a near frenzy, playing on their rustic gullibility as on a fine instrument. It had been a long night, but it seemed that things were drawing to a finish.

The knife was equally theatrical, thirteen inches of flashing steel, wielded with artistry in order to catch the torchlight. For nearly twenty minutes it had flickered and dipped over my supine body, brushing my skin like a lover, leaving behind thin threads of scarlet as it lifted; my eyes ached with following it about. Still, I couldn’t very well shut them; the mind wishes to see death descend, however futile the struggle.

But it would not be long now. I did not understand most of the words so dramatically pelting the crowd, but I knew they had something to do with evil spirits and the cleansing effects of bloodshed. I watched the motions of the knife closely, saw the slight change in how it rested in my attacker’s hand, the shift from loose showmanship to the grip of intent. It paused, and the man’s voice with it, so that all the village heard was the sough and sigh of the torches, the cry of a baby from a nearby hut, and the bark of a pi-dog in the field. The blade now pointed directly down at my heart, its needle point rock-steady as the doubled fist held its hilt without hesitation.

I saw the twitch of the muscles in his arms, and struggled against the chains, in futility. The knife flashed down, and I grimaced and turned away, my eyes tight closed.

This was going to hurt.

But as the knife began its downward descent, as the mechanical device now built into the bottom of the upturned cart clicked open and gave way, as the lit pyrotechnic sputtered in my ear, my eyes flew open again, for in that brief instant, a stray splash of light had illuminated a pair of figures at the back of the crowd. But I was too late: By the time my eyes came open again to seek them out, the trick knife had collapsed against my body and I was dropping to the rocky ground beneath the cart, artificial blood flying all over and the flash blinding everyone but Holmes. Cursing furiously under my breath, I shook free of the chains, fighting to turn over in the restricted space without overturning the cart and giving myself away, while Holmes raised his voice above the sudden clamour that the flash always stimulated, telling the villagers that the sacrifice had been taken up by the gods. I pressed my bare eye to the side of the cart where a small crack let in the torchlight, searching for the figures.

Even without my spectacles, the turbans caught my eye: red and high, with a gleaming white device over the forehead; and beside them, a smaller, bareheaded man, his features indistinct—but I didn’t need to see them.

The maharaja of Khanpur had caught us up.

There were more guards, I saw, closing in on our rustic stage as the villagers faded quickly back behind the protection of their walls. I lay hel

pless, waiting for strong hands to lift the cart and drag me away. But to my surprise, the maharaja seemed more interested in Holmes than in me.

“How did you do that?” he asked, speaking Hindi.

“Oah, my lord, it is the Arts,” Holmes replied.

“It is trickery.”

“My lord, no trickery. I am a follower of the Prophet, but my skill is in the hands of Vishnu and Shiv.”

“I wish to see it again.”

“I will happily come to your court and—”

“Good,” the maharaja said, and turned away. I let out the first breath in what seemed like several minutes, but too soon. The prince’s hand came up in command, and through my thin crack I saw figures in red puggarees closing in on the cart—or rather, on the cart’s owner. Holmes had only time enough to bend over where I lay and speak what sounded like an incantation, but which was actually a command, in German: “Stay there, then go for aid.”

There was a scuffle and Holmes’ querulous voice demanding explanation, followed a minute later by the sound of a motorcar starting up. Then, awfully, silence.

Chapter Twenty-One

I crawled out from beneath the shiny wagon, rubbing unconsciously at my wrists and at the bruise on my hip that came with every fall through the trap-door. What the hell was I supposed to do now? I asked myself. We’d avoided the maharaja because we feared he might recognise me; we hadn’t even considered that he might go to the effort of hunting down a magician to add to his collection, however temporarily.

I pulled my spectacles from my pocket, but clarity of vision had little effect on clarity of thought. Holmes had said, “go for aid,” which meant that he didn’t think I should wait around for him to be returned. “Aid” could only mean Geoffrey Nesbit, but even if the man was at home in Delhi, it could take him days to get here. And I couldn’t see that walking openly into a telegraphist’s to send a message would be the most sensible action: Clearly, the maharaja had ears throughout his country, or he’d never have found the magician Faith had seen in Khanpur city.

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

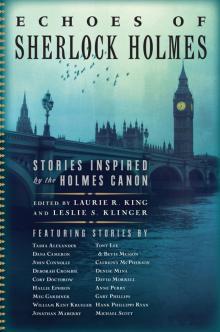

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1