- Home

- Laurie R. King

Garment of Shadows Page 3

Garment of Shadows Read online

Page 3

I lowered my head to my knees, trying to think back over the day, trolling my memory for any kind of clue. I was in a North African city made up of an un-mappable tangle of tiny by-ways. Some of its buildings took the breath away with their beauty, their ornate tile-work crisp, their paint and carvings clean. Other houses were rotting shells on the edge of collapse, dangerous and stinking of decay.

One might almost think my damaged mind had created a town in its image.

Enough, I decided. I could do no more tonight. I was dimly aware that one was supposed to keep a concussion victim from sleep, but in truth, given a choice between staying awake any longer, and simply not waking up, I would take the risk.

I laid the decorative knife beside me on the cushion and tugged the hood over my face. As the world faded, again I smelt the faint aroma of honey.

CHAPTER THREE

The clipaclop of a donkey’s hooves woke me. The room was black as a bowl of tar—but no: A faint glow came from one corner. Not a windowless cell, then; but where …?

Donkeys. The odour of smoke, and wool. A memory of mint on the tongue: the suq. I started to throw off the bed-clothes, discovering simultaneously that there were no bed-clothes and that my head strenuously objected to sudden movements. My fingers tugged at the rough wool, found it was a garment—ah, the brown robe from the hook in the small room. With that, the previous day slid into place: the dappled reality of wandering a labyrinth of dim, tight foot-paths, as if I had been set down into a world of tunnelling creatures. Into a beehive.

Shadowy streets and a shadowed mind.

Still.

I sat, pushing the robe’s hood away from my face.

The concussion hadn’t killed me, then. It was early: No light came from the high window. My surroundings had remained silent during the still hours, with no evidence of living quarters overhead, although after I had thrown more coal on the fire, the cat had roused itself for a bit of mouse-chasing before coming to settle beside me. And I dimly remembered a long echoing prayer, or song, as if some insomniac muezzin had decided to enforce the declaration that prayer is indeed better than sleep.

Despite that interruption, I felt rested. The pain in my head remained sharp, but the rest of me merely ached. I patted around the floor until I encountered my spectacles, which had been ill-fitting to begin with and were not improved by having been used as a lock pick: One of the lenses bulged against the frame, and the right earpiece had several unintended angles. I folded them away into my pocket, and raised my fingers to the turban I wore.

Not, I thought, precisely a turban. The cloth encircling my head felt more like a bandage, although with the robe’s hood up, it might look like an ordinary piece of head-gear—ordinary for this town, that is, but for a lack of the thin pig-tail many of the men wore. The part of my skull over my right ear seemed the most tender, which was perhaps related to the kink in the earpiece. All in all, I would leave the wrap in place for now.

Light would help. I dug into my garments for the box of French matches, which I had pocketed after lighting the oil lamp in yesterday’s cell. They were mashed rather flat now, since I had lain on them all night. There must be some kind of a lamp here. I stood, and as I did so, some small metallic object flew away from the folds of my clothing, rolling across the stones. I stifled the urge to blindly leap after it. Instead, I felt the remains of the box: three matches.

I lit one on the second try, and held it above my head. The flame burned out before I reached the lamp it had revealed, but I felt the rest of the way in the darkness. After giving the thing a slosh, to make certain it held fuel, I scratched my second match into life and nurtured the lamp to brightness.

A myriad of gleaming shapes shone back at me: stacks of brazen bowls, trays ranging from calling card–sized to sufficient for an entire roast sheep, bowls of similar variety, a dozen shapes and sizes of lamp. But the one I carried seemed to be the only one holding oil, so I took it in search of the rolling object.

There was a hole in the floor, a drainage hole (no doubt the source of the wildlife that had entertained the cat during the night) containing sludge so disgusting, not even the Kohinoor could have tempted my hand into it. Before I made the laborious effort of climbing back to my feet, I studied the shape of the stones themselves. Yes, a carved trough led towards the hole, but a settling of the paving stones suggested an alternative route, directly towards a workbench that rested on the floor. I set the lamp on the stones and laid my cheek to the floor, the cool stones startling another snippet of memory to the fore: cold stones/the lit crack beneath a door/red boots/a fire/rhythmic speech—

And then that, too, was gone.

But there was something small and shiny, under the bench.

My fingertips teased at the round smooth gleam, threatening to push it away for good. I sat back on my heels and reached for my hair, finding only fabric where my fingers had expected hair-pins. But, I did have one pin. I found it in my pocket, bent it into a hook, and pulled the elusive circle out.

A gold ring, accompanied by a sharp hallucinatory odour of wet goat. It was not the one missing from my own hand, for it was big enough around to fit my thumb. A man’s signet ring, very old and, judging from its weight and colour, very valuable. I held it to the lamp-light to study the worn design on its flat edge: a bird of some kind, a stork or pelican, standing on wavy lines that indicated water.

Not a thing one might expect to find in the shop of a brass-worker. But then, neither was it the sort of jewellery one might expect in the pocket of an amnesiac escaped circus performer.

But a pick-pocket? One who had run afoul of the police?

Or, did it belong to my missing husband?

I set the lamp on a clear patch of bench, and emptied my pockets down to the fluff.

I picked up the embroidered purse, noting that the clasp was still shut—the ring could not have fallen from there. I poured its contents out onto the age-old wood, coins and currency, all relatively new. BANQUE D’ETAT DU MAROC, they said, CINQ FRANCS; the coins were stamped with EMPIRE CHERIFIEN, I FRANC and 50 CENTIMES. One marked 25 CENTIMES had a hole in its centre.

So: Morocco.

I corrected myself: More exactly, this purse had been filled in Morocco. Still, it was evidence enough to be going on.

And the Arabic numbers, along with the spectacles and the modern rifles the soldiers had carried, suggested the twentieth century rather than the nineteenth—or the thirteenth.

Absently, I rubbed the currency about on the filthy wood, then crumpled it before returning it to my pocket: unlikely that someone with my current appearance would possess crisp, new bills.

In addition to the bits and bobs I had appropriated the day before, I found the following:

In the trouser pockets, grains of coarse yellow sand.

In the left-hand pocket, a chalky stone the size of a flattened walnut.

From the right-hand pocket I took a length of twine, snugly bound, and an object wrapped in a handkerchief. I unwound the worn muslin to reveal a length of copper pipe, four inches long and an inch across. The handkerchief was permeated with sand. Beneath the creases I made out the crisp lines of a long-ago ironing, but there were no convenient monograms or laundry marks. I examined the pipe; it contained only air. But when I wrapped it back in the cloth, then laid the bundle across the fingers of my right hand, they closed comfortably around it.

My left hand remembered all too vividly the sensation of driving a knife through flesh. My right hand, it would seem, provided the support of brute weight.

So: a pick-pocket accustomed to nasty fighting.

Had I killed a man to steal his ring?

I dropped the primitive knuckle-duster into its pocket, then took a closer look at the quartz-like stone. Other than being of sedimentary origin, and vaguely reminding me of building material although it was of a size that more invited the hand to throw, it told me nothing—my store of odd knowledge apparently did not include petrology.

The stone and everything else went into the pockets they had come from, with the exception of a handful of dried fruit, the decorative knife, the empty purse, the scissors, and the ring. The fruit I ate; the empty purse I tossed onto the brazier coals, pushing it down with a stick; the rusted scissors, which had jabbed me continuously the previous day, I abandoned on a high shelf; the ring I sat and studied.

The problem was, everything I took from my pockets had seemed possessed of immense mystery and import, as if the stone, the pipe-length, the grains of sand were whispering a message just beneath my ability to hear. When everything meant nothing, it would appear, even meaningless objects became numinous with Meaning. The date pip I spat into my palm positively throbbed with significance.

It was damned irritating.

Another donkey went past, a reminder that daylight could not be far away. I had to leave this place, lest I be driven to make use of that pipecosh and the stolen knife.

First, I rescued a length of leather from a stack of the same—polishing rags, it would seem—and fashioned a rough wrist-scabbard for the stolen knife. I took a last look at the ring, sitting by itself on the workbench, then caught it up and dropped it into my breast pocket.

My hand stopped. Breast pocket: I’d forgotten I had one.

It was the size of my palm, with a flap, currently missing a button. I fished around inside, feeling its emptiness—and then a faintly non-cloth sensation brushed my fingers. I drew out a tiny scrap of paper, smashed flat by having been slept upon.

I picked it open. The paper was near-translucent onionskin, and had been wet at some point, but I managed to get it flat with only a small tear: the corner of a larger page, a triangle three and a half inches high and two and a bit wide. There were a series of pencil squiggles on it, lines as pregnant with meaning as the grains of sand and the date pip:

It looked like a capital A drawn by a small child or the victim of a stroke, although oddly precise. Probably it was the result of a piece of paper and a stub of pencil riding together in a pocket.

I turned the scrap over. Then rotated it.

At first glance, the string of interconnected curves seemed as devoid of meaning as the accidental A on the reverse. But I knew they held some intent beyond mere idiotic self-importance, and indeed, once I shifted the direction of my gaze to read from right to left, the pencil scribble became words, in crude, even childish Arabic writing: the clock of the sorcerer.

I sighed.

Pressing the scrap into my purloined note-book, I put it and the ring into the breast pocket, stitching the flap shut with the ever-useful hair-pin. I arranged the cushions as I had found them, pushed the purse’s metal clasp deeper into the coals, and blew out the small lamp. When I had let myself out, I padlocked the door and walked into the suq in search of a sorcerer and his clock.

I found many things during the course of the day. My first goal was food and drink, followed by thick stockings and a heavy woollen burnoose to keep out the penetrating cold. As I walked, the chorus of muezzins woke the town, and soon the streets burst into life, shutters opening to displays of colour and enticing aromas—not the least of which was the damp soap-smell that wafted from a hammam, a place I dared not even think of entering, no matter how much the pores of my skin craved a scrub-brush.

By mid-morning, I was warm, fed, and gaining in confidence: I had negotiated several transactions without arousing suspicions, I had passed two more pairs of patrolling armed soldiers, and my tongue was producing a reasonable facsimile of the local accent. Yes, a restoration of memory would be nice, but as the immediate needs of survival became less pressing, the suq provided an endless variety of distractions, for all the senses: I saw tailors and carpenters, carpet-makers and silk-weavers, book-binders and jewellers, purveyors of leather footwear and ceramic pots and elaborate wedding head-dresses, men embroidering the fronts of robes or trimming the beards of reclining customers. My nostrils were teased by the odours of frying onions and baking bread and the cloud of aromas from the spice merchants, in between being repelled by the miasma from butchers’ shops and malfunctioning sewers, entertained by the sharpened-pencil smell of fresh cedar and the musk of sandalwood, caught by the clean reek of fresh leather or the dark richness of roasting coffee beans, and educated by the contrasts of wet plaster with crushed mint, donkey’s droppings overlaid by fresh lavender. My ears similarly passed from one aural environment to another: a chorus of schoolboys from over the walls of a madrassa and the sound of a grain mill grinding below street level; the rhythm of soft-soled footwear against compacted dirt beside the ceaseless, many-noted ting of brass hammers from a dark den; a pure voice raised in song giving way to the rasp of small saws from an inner courtyard.

The populace ran the spectrum from African black to Mediterranean olive, with the occasional Nordic features and even blue eyes looking out of Arab brown skin. Jews, Arabs, Europeans, Sufis, each in a different form of dress. Transportation was mostly tiny sweet-faced donkeys and sullen mules, but I also saw a few horses, a handful of wheel-barrows, two camels (at a distance, not within the suq streets), and one heavy-laden, flat-tyred bicycle being used to deliver lengths of bamboo.

And the wares on offer! One street held shops displaying tall cones of varicoloured powder, from the deep red of paprika to brilliant yellow turmeric, interspersed with vendors selling bags of sticks, leaves, seeds, and what appeared to be sand, bowls of dusty blue chunks of indigo, and carefully arranged hillocks of mice skulls and desiccated lizards. One shop displayed hundreds of prayer beads on its three walls—ivory and amber, lapis and coral, sandalwood and ebony. Its neighbour held teetering stacks of cylindrical tarbooshes, or fezzes, mostly red, with tassels of every colour imaginable.

Few of the shops had signs. I took care to read any that did, and once spotted the word horloge on a display of timepieces near a gate at the southern edge of the suq, but there was no mention of sorcerers.

Apart from the absence of magicians’ timepieces, the town held a richness of sensory stimulation and information, when a person had nothing to do but wander and listen. And as the morning wore on, I found that the previous day’s sense of confusion had settled considerably.

I was, I determined, in Fez, a walled Moroccan town built where the hills meet the plains. Water was all around; wherever I walked I could hear a rush or a trickle, and decorative fountains in various states of repair and cleanliness were on many corners. Now that daily life was under way again, the flow of traffic (all either pedestrian or four-legged) led me from one neighbourhood to another, each centre composed of a mosque and its attendant religious buildings, food markets, a baker’s oven, and the ever-tempting hammam baths. Specialised craftsmen clustered in given areas. As I made my way north out of the central mosque district, I found that even the more general tradesmen—grocers, tailors—tended to gather together, interspersed with stretches that were largely residential.

Some of the streets were packed with furious activity—men bearing loads, women haggling for greens, and artisans creating tools for daily life; other streets stood in a state of suspended animation, with nothing more lively than a sleeping cat (I saw no dogs, but then, this was a Moslem country). Earlier, the rooftops had brought to mind a honeycomb; now, the streets around me evoked the life within a hive, some corners almost deserted, others bustling with the same sense of incomprehensible purpose.

I continued north until I came to the city walls, and another gate. There I spooned up a bowl of harira that tasted entirely different from yesterday’s, followed it with a bowl of spicy fava beans swimming in oil, made my dessert out of three sugary dried figs, then bought a handful of pistachios and perched on a bit of collapsing wall in front of a Moroccan druggist’s shop, tossing away the shells and watching the French guards.

Sitting before the gates brought an odd sensation. I did not think that I had ever been there before—certainly there was no sense of memory attached to the scene—yet it was deeply familiar: the wall, the ga

te, and the guards; the aged olive tree overhead, under which women sat with their children and rested before carrying their burdens to homes outside the walls. A water-seller with tiny tinkling bells filled cups with water from a swollen goatskin slung across his shoulder (the sight stimulated another sensory rush: taste of metal/mouth filled with warm and musty water/two dark companions and then it was gone). A fortune-teller drowsed on one side of the gate, waiting for customers; on the other side, a blind storyteller sat in a patch of sun against the wall with a dozen children at his feet. The storyteller was too far away to hear, but still a voice seemed to murmur in my ears, in another language …

Hebrew. In the square before the Water Gate … those who sit at the gate … at the threshing floor by the entrance to the Samarian gate … in the gateways of the city, Wisdom makes speech.

I found myself smiling at this transferred image of city gates where, since time immemorial, the people of a town gathered, for news and flirtation, sanctuary and entertainment, food, drink, and the dispensation of justice, all under the close watch of the guard.

And these guards were attentive, give them that. The soldiers eyed every person going in or out. Those with loads, on their heads or strapped to beasts, were examined more closely. A man with a donkey laden high with greenery from the fields—at least, I assumed there was a donkey beneath the green mountain, though all I could see were hooves and an ear—had to pull bits off before he was permitted to drive his beast onward. The only time the guards relented was when a weary and travel-stained family came to the gate: a pregnant woman, her mother, and a very old man, with three children, the oldest a boy of perhaps ten. The ancient man was balanced on a donkey that looked as old as he; the family’s worldly goods were carried in ragged bundles by even the youngest, a child no more than three. This group of travellers the guards treated gently, with a nod of respect for the ten-year-old head of the family, a pat on the head-scarf of the little girl. The family went by, their eyes locked into the faraway stare of those who have watched more than they could take in. Refugees?

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

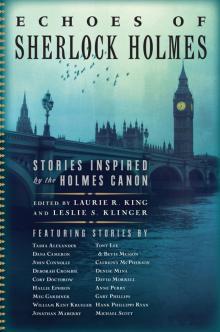

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

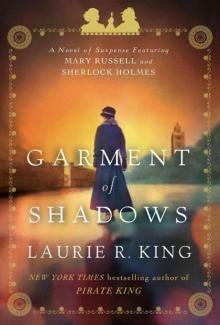

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1