- Home

- Laurie R. King

A Grave Talent km-1 Page 30

A Grave Talent km-1 Read online

Page 30

"A last question, Miss Vaughn," said Grimes, casting about in desperation for a quote with some zing to it. "I'm curious about your name change. Did you have any reason for choosing the name Eva Vaughn?"

This unexpected question caught Vaun's attention, and for the first time she seemed to look at him.

"Adam and Eve were the same person, weren't they? Two halves of a whole. It wasn't really a name change at all."

"Are you a religious person, then?" Grimes tried not to sound surprised, as if Vaun was about to declare herself a born-again believer, and at that she fixed the full gaze of her remarkable eyes upon him and smiled gently.

"Not church-religious, no. But a person who has been through what I have is not apt to find such thoughts… without interest."

The camera flashed a final time, and in three minutes they were back on the freeway, going north. The driver went off on the second exit, drove east for a few miles, and joined the other northbound freeway. Hawkin nodded and eased his neck. No followers.

Kate leaned forward in her seat, and Hawkin half twisted to talk with her.

"There were television people in that lot at the pier," she noted. "How much do you suppose they'll put on tonight?"

"They're sure to have something. Saturdays are always slow."

"Anyway, Lee and I will stay inside from now on, as there's sure to be people wandering up and down the street. Hopefully it'll be a couple of days before one of the neighbors squeals on us. Lee has to go out tomorrow afternoon to see one of her clients at the hospice, and she has two people coming to the house, one tonight and one Monday night, that she really doesn't want to put off. The rest she's cancelled. Is that okay?"

"Let the guys across the street know exactly who they are and when they're coming, so they don't get nervous. There's no point in locking yourselves off entirely, so long as—" He stopped with a look of astonishment, and Kate jerked around to look at Vaun.

She had broken, at last. Her eyes were shut and her mouth open in a little mewling o, and she was trembling. Her hands came up to cover her face, and she twisted toward Lee, who held out her arms, and Vaun went blindly into them and curled up as best she could, with her head in Lee's lap, and with Lee's arms and upper body bent fiercely around her. She huddled there all the way home, and Lee rocked her and murmured to her. The others sat silent with their thoughts.

Vaun spent the rest of the afternoon upstairs. Lee cooked, making croissants from scratch and an elaborate salade niçoise with fourteen separate marinated ingredients that took her several hours and filled the kitchen with pans, and might have been iceberg lettuce with bottled dressing for all any of them tasted it. Kate prowled the house until her nerves were jangling, and finally disappeared into the basement to pedal the exercise bicycle for an hour. She came up dripping and had a glass of wine, showered and had another glass, and watched the local news, including the amateur videotape of the backs of three blurred women, after which she felt like having several more glasses but did not.

When the news was over Lee went upstairs with a glass of whiskey, which she made Vaun drink, and then came back and set out the dinner, which they all picked at. Finally she took the food away and went to make coffee. Kate and Vaun cleared the table, but to Kate's surprise Vaun, instead of retreating upstairs, went to sit on the sofa. Kate obligingly laid and lit a fire and wondered if Vaun just wanted company. She fetched the coffee tray and poured them each a cup.

"Do you feel like a game of chess, or checkers? Backgammon?" she offered.

"No, thanks. I'd like to tell you something, you and Lee. Something about myself."

The hum and swish of the dishwasher started up in the kitchen, and Lee came in for her coffee. Vaun rattled her cup onto the table and got up to make a silent circuit of the room, touching things. When she got back to the sofa she folded herself up into it and simply started talking. For the next two and a half hours she talked and talked, as if she had prepared it all in advance, as if she never intended to stop.

31

Contents - Prev/Next

"I cannot remember a time when my hands were not making a drawing," Vaun started. "My very earliest memory is of a birthday party, when I was two—I have a photograph that my aunt sent me four or five years ago, and it has the date on it. One of my presents was a box of those thick children's crayons and a big pad of paper. I remember vividly the sensation of pulling open the top of the box, and there was this beguiling row of eight perfect, smooth, brightly colored truncated cones, lying snugly in the cardboard. They had the most exciting smell I'd ever known. I took one out of the box—the orange one—and I made this slow, curving line on the pad. There were all these other presents sitting piled around me, but I wouldn't even look at them, I was so fascinated with the way the crayon tip made this sharp line and the flat bottom made a cobwebby wide rough line, and how I could make a heavy line of brighter orange when I pushed hard, and the way it looked when I scribbled it over and over in one place. I can still see it, my fat little hand clenched around that magical orange stick, and the thrill of it, the incredible excitement of watching those lines appear on that clean, white paper.

"My poor mother, she must have looked back on that day with loathing. Everything she hated, everything she feared, there it was, welling up in her sweet, curly-haired, two-year-old daughter."

Vaun smiled crookedly and leaned forward to refill her cup. She put down the pot and poured a dollop of cream into the black liquid, where it billowed up thickly to the surface. She watched intently the color change, her mind far away.

"My mother was born in Paris, just after the First World War. Her father considered himself an artist, but he had absolutely no talent, other than for latching on to real artists and drinking their wine. He and my grandmother weren't married, but she put up with him until the winter of 1925, when my mother, who was about six, nearly died of pneumonia from living in an unheated attic. Grandmother decided to emigrate to California, so when he was out at a weekend party in the country she gathered up all the presents he'd been given, or helped himself to, including several respectable canvases, sold them, and bought passage for herself and my mother to New York. It took five years to work her way to San Francisco, but they made it eventually. She married when my mother was twelve, and had two more children, Red and another daughter who died young, but she never let up on her first child and drilled into her the unrelenting image of an artist as someone who steals, drinks, and is willing to allow his own daughter to die of neglect in his self-absorption.

"In due course my mother married a man who was as far from the art world as she could get. He was an accountant. He rarely drank, his parents lived in the same house they'd bought when they were first married, and he hadn't been inside an art gallery or museum since high school. Utterly stable, unimaginative, twelve years older than my mother, completely devoted to her, and, I think, somewhat awed by her sharp mind and beauty. A good man, and if he wasn't exactly what my mother needed, he was certainly what she wanted. The snapshots he took of her in those early years show a happy woman. Until my second birthday. They didn't have any other children, though as far as I know there was no physical problem. And I never had another big birthday party—she was probably afraid of having someone give me a set of paints or something.

"Of course, at the time I knew nothing of her background, why she so furiously hated my obsession with drawing. I was probably too young, even if she'd tried to tell me, but she never did try. It was only recently, about five years ago, that I finally pieced it together."

"And how did you feel about it?" Lee asked curiously.

"Vastly relieved. When I was young I thought it was my fault, and that my inability to control myself led to their deaths. Later I put it onto her, and it seemed to me that she was a sick, jealous woman. After I dug out the truth and learned about her parents, I felt a tremendous relief. It wasn't my fault, it wasn't even her fault. It was inevitable, perhaps; certainly acceptable.

"I wond

er too if her phobia didn't drive me more deeply into it. It would have been there anyway, but perhaps a more gentle, natural talent. As it was, her continual attempts to distract me, find other interests, pull me away from my crayons and pencils served only to make me more completely single-minded. I wasn't interested in toys; I didn't want to play with other kids; I just wanted to draw. Before I was four, the lower half of the house walls were a disaster, and nobody could put down a piece of paper or a pen without my making off with it. I can remember having a screaming tantrum one day when she tried to get me past the crayons in the grocery store. It must have been one unending nightmare.

"When I started going to nursery school, at about four, at first the teachers were overjoyed with this little kid who could do the most amazingly mature drawings. After a few weeks, though, they got very tired of fighting to drag me out into the playground, or sit and listen to a story, or do all the things normal, well-balanced kids do. That's when I started going to a psychiatrist.

"I must have gone through a dozen of them in the next couple of years. The earlier ones were mostly women, and looking back I think that at first they all figured that I just needed a firm hand and an understanding ear. When that made no difference they'd begin to suggest that perhaps they should be treating Mother instead, and soon I'd go off to another one.

"When I was about five, maybe six, they began to be men, rather than women, and older, and more serious. I remember asking my mother once why some of them had framed pictures on their walls that had only writing on them, and she explained about diplomas and the like.

"Finally, when I was seven, we met Dr. Hofstetter. He had a whole wall of framed diplomas and letters in his waiting room, and I was intrigued with the pattern of the black frames against the white paper and the beige wall. Four of them had red seals, beautiful symmetrical sunbursts that leapt out from the wall, the color of blood.

"I spent several months with Dr. Hofstetter, talking about what I liked to draw and looking at books, and finally he must have decided that radical therapy was needed, because one afternoon my father took me out to a movie—it was the beginning of summer vacation—and when we came home there was not a single writing instrument in the entire house. No crayons; no paint; no pens, pencils, or chalk. I was furious. They had to use tranquilizers to get me to sleep that night. The next morning I poured my porridge onto the table and drew in it, so my mother started to feed me by spoon. If I went outside I'd use a stick in the dirt, so I stayed in. I made patterns with soap on the bathroom tiles, so I wasn't allowed to bathe myself.

"I stood it for five days. I just couldn't understand why they were doing it to me. It was like being told not to breathe. I felt like I was going to explode, and finally on the sixth day I wouldn't get out of bed, wouldn't eat or drink, and wet myself. Mother bundled me off to the shrink, who tried to explain that it was for my own good. I just sat there, staring straight ahead, not really hearing his voice, and finally he gave up and led me out to the waiting room while he and my mother went into his office. I could hear their voices, hers very upset, and his receptionist in the next room typing and making telephone calls while I sat there in the stuffed chair and looked at the pattern of the frames on his wall, and the red sunbursts.

"As I sat there, alone in the world with those seals, they began to bother me. They were wrongly arranged, out of balance, and the more I studied them, my mother's voice rising and falling in the background, the more they bothered me. It needed another spot of red, just up there, on the upper right, above the sofa, and I reached in the pocket of my coat for my crayons, but of course they weren't there, and I thought of going in and finding something in the secretary's desk, but I knew she would stop me, and there was that unbalanced arrangement of red seals waiting for me to do something about it, and I had to do something—I couldn't stand it, sitting there with those lopsided marks dragging at the wall—so I did the only thing I could think of, which was to stand up on the sofa and bite my finger, and use that."

She paused in the deathly silence and looked down at her hand, and rubbed her thumb across the pale scar that curved across the pad of her right index finger.

"That was the end of psychiatrists for a long time. My father came into my room that night, with a paper bag. He sat on the side of my bed and he opened the bag and took out one of those giant boxes of sixty-four crayons, with silver and gold and copper, and a real artist's pad, thick, textured paper. He put them on my bedside table and he crumpled the bag into a twist and he started talking to me. He told me that artists needed wide experience to do their art properly, that anyone who never looked up from the paper soon had nothing to draw. Therefore he would make a deal with me. I could draw and paint for one half hour before school in the morning, for two hours in the afternoon, and for one hour after dinner if I would agree to pay attention in class, play outside at recess time, read, and do my homework. If I agreed to this, and if I stuck to it, I could begin to have lessons on the weekends. He was a very wise man, but he was not very well and was totally intimidated by my mother most of the time. His compromise stuck, and that was how I lived for the next six years, until they were killed."

Vaun looked at the flickering fire for a long moment and shook her head.

"My poor mother," she said again. "If she had lived… But I would be a different person, not Eva Vaughn at all. They died when I was thirteen, in a stupid boating accident—the man at the helm was just drunk enough to make a mistake. I went to live with Red and Becky, my mother's normal half-brother and his normal wife and two nice, normal kids, aged nine and eleven. They were totally unprepared for someone like me dropping into their life—smack into puberty, terrified at losing my security, and filled with anger at my parents and a guilt that I couldn't express, awkward and ugly physically, and saddled with this all-consuming obsession that nobody could understand and I couldn't even begin to talk about. I moved three hundred miles away to a small farming town, into a school with overworked teachers, kids who'd never even known an adult artist before, much less a weird kid their own age—and, of course, no more weekend lessons.

"They tried, my aunt and uncle, they really did, but they didn't even know where to begin. I bullied them into giving me a shed to paint in, and before long I just lived out there. I tried, too, when I thought about it. I took over a number of jobs around the place to make myself less of a burden. When I was sixteen I began to babysit around the community, to earn money for my supplies. I built a box to hold my paints and small canvases, and I was happy to cover a kitchen table with newspapers and work until the parents got home.

"For about six months I was happy, really happy. I had money for paint, my aunt and uncle had decided hands off until I was old enough to leave, school was easy enough to be undemanding, and the local librarian was very good at finding me books on art theory and reproductions to study. At seventeen I began to think about going to college. My grades were decent, there was a small settlement left from my parents' death to get me started, and I was putting together a portfolio that I thought was not too bad. With my uncle's approval I sent in applications to three universities.

"It was an exciting time. I was in my last year of what I thought of as exile, and I could see that my work was good, that I had a future waiting for me. These were the early seventies, and even in rural areas the times were exhilarating. Then in December of my senior year two things happened: I slept with a young man, a couple of years older than I was, and he introduced me to drugs. Andy Lewis. It was part of the whole package, you know. If you looked like 'one of those hippies,' it meant you did drugs, so I did. For six months I did, mostly grass, but twice LSD. The first time was in December.

"The acid was interesting. It changed the way I saw colors and intensified the vibrations of different colors, the glow everything gives off. Not only while I was under the influence but for a couple of weeks until it faded back to normality. And in the middle of March when Andy offered me another tab, I took it.

"It was bad. I don't know why it was so different from the first time, but I just went insane. A little while after I swallowed the stuff I was sitting and looking down at my hands. There was a faint smear of red paint on my finger, near the scar, and as I watched it suddenly started smoldering and bubbling and eating into my finger and exposing the bone, which turned into a white bristle brush—" She broke off and looked up sheepishly. "There's no need to go over all the bizarre details, but in the end what happened was that my fingers turned into brushes and when I looked at one of the guys there—not Andy, I don't remember him being there, it was one of the kids who used to hang around—I saw paint pumping through his body, pulsing, every color, brilliant and iridescent. I was trying to get at the paint in his throat when the police arrived, and after I attempted to throttle several other people, they hauled me off to the hospital and filled me with some kind of heavy-duty tranquilizers. It was a lot of excitement for our little town, as you might imagine.

"By the next morning I was okay—sick and covered with bruises, but my fingers were flesh and blood again. They let me go home later, and the following day I was carrying a pan full of hot soup across the kitchen and felt my fingers turn to wood and dropped the pan. I had half a dozen relapses— sometimes I'd see paint pulsing in one of my cousins—but gradually it tapered off in frequency and intensity. I swore I'd never touch anything again, and bit by bit my family began to relax.

"In the first week of May I received a letter from one of the universities, the one I badly wanted to go to, saying that if I wished to send some samples from my portfolio I would be considered for a freshman scholarship in the fall. I went through the stuff I'd been doing, and somehow it didn't look as good as I'd thought it had. The next day I laid it all out, and I was appalled. I'd done nothing but crap since January. There was not one piece that wasn't sloppy and careless, and what was worse, it was all false, pretentious, shallow. Typical druggie stuff. I flushed the various leaves and tablets down the toilet and that afternoon told Andy to take a jump and got to work.

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

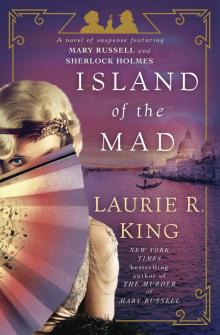

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1