- Home

- Laurie R. King

Justice Hall Page 4

Justice Hall Read online

Page 4

Mrs Algernon directed us into a wood-panelled chamber with a fire in the grate, a room lifted straight out of a Mediaeval manuscript. We deposited him on a bed not much younger than the house and left him to the scolding ministrations of his housekeeper.

Back downstairs, with fresh logs on the fire, fresh coffee warming in front of it, and a dusty bottle of far-from-fresh brandy standing to one side, I studied my surroundings again, looking for I knew not what clue.

“What are we seeing here, Holmes?” I asked. “If you’d told me that Ali’s past was . . . this, I’d never have believed you. How do you explain the complete shift in the man—not just his speech patterns and how he moves, but his basic personality? The Ali we knew was short-tempered and as stand-offish as a cat. He’d have been at death’s door before he allowed us to carry him up a flight of stairs—or for that matter, before he’d have come to us for help in the first place. This is a completely different man.”

Holmes nodded. “One can only assume that when he went to Palestine, Alistair Hughenfort created the image of an entirely new person, and then stepped into that image. Now he is home, his original persona has taken over again. You’ve done it yourself, Russell, when you are in disguise. It is akin to complete fluency in two languages; one moves from one to another with no pause to consider the changes.”

“Holmes, I realise that clothing makes the man, but this is a bit . . . extreme. To assume a disguise for days, even weeks, is one thing. He was Ali Hazr for, what? Twenty years? And it wasn’t as if he went out to Palestine as a disguised government agent in the first place—he and his cousin must have been out there for some time before Mycroft claimed them. What could drive a man to tear up what are quite obviously deep roots in order to become a foreign nomad?”

At that question, however, Holmes could only shake his head.

CHAPTER FOUR

Most unusually, I was awake the next morning before both Holmes and the sun. Before anyone, I thought as I padded down the time-worn steps with my boots in my hand—but no; once in the panelled vestibule beneath the minstrels’ gallery, kitchen noises of clatter and conversation came from behind the doors on the other side of the dining room. I hesitated, mulling over the appeal of a cup of tea, but decided my thirst for solitude was greater.

Frustration had awakened me, had in fact been my restless companion all the night, an impatience to act, or even to know what it was that we were being called upon to do. I had, I realised, been working for ten weeks straight at this profession I still thought of as Holmes’; like a turning flywheel, the momentum of activity was hard to slow.

The massive bolt on the front door slid easily back, and a wash of frost-tinged air poured in. As near as I could see in the half light, the porch and yard beyond were free of people and slumbering dogs. I slipped out, eased the door shut behind me, sat on the porch bench to lace on my boots, and set out into the fresh, pre-dawn twilight.

Traces of mist hung over the land, but it was high enough that it did not obscure my half-seen surroundings. My boots crunched over tightly packed gravel to a break in the walls between the corner of the house and a small building I took to be a church. Once I was through the gap, the surface changed from gravel to grass, and my footsteps ceased to jar the air.

I wandered among the half-bare trees of a walled orchard, enjoying the ancient, sleeping garden, my feet raising the scent of fermenting apples from the slick, black blanket of fallen leaves. I crossed into a large kitchen garden, also walled, of which less than half seemed to be actively under cultivation, and saw a wooden door on the far wall. This opened onto a water meadow, the stream at its bottom bridged by a small structure that shuddered, but did not collapse, beneath my weight. The air lay so still on the land, it was like walking out into a painting.

I made my way through the soft pearl of gathering light, heading in the direction of a tree-capped rise glimpsed in outline perhaps half a mile away. The air smelt of grass and sheep and earth: no sea breath here, as at Sussex, no peat tang as in Devon. This was the growing heart of England, deep black soil that had been nourishing crops and cattle for thousand upon thousand of years, before Normans, or Romans, or even Saxon horde. As the sun’s rays began to touch the high mist overhead, I noticed what appeared to be a bench at the top of the hill, just under the edge of the cow-cropped branches. I clambered over a stile and trotted up the side of the hill, brushed a layer of fallen leaves from the rustic bench, and settled onto the damp wood to watch the sun come into the fold of earth that held Alistair Hughenfort’s quintessentially English house.

The cool streaks of mist shied away at the merest hint of sun; soon my hilltop was fully lit. After a minute, the first rays lighted on the tips of three Tudor chimneys, easing like cool honey down the lumpy brick-work to the neatly thatched peaks. The many-paned windows set into the half-timbered upper level of the house flared now into a mosaic of light; when the line of the sun made a neat division between the house’s two storeys, an upstairs window flew unexpectedly open. The depths of the walls kept the light from falling on the figure inside, but I felt that someone stood for a few moments in whatever room lay behind the window, looking out, and then went away.

The house was stirring, but I did not. The sun felt delicious on the side of my face, bright with promise and the illusion of warmth. The vista before me, this intimate and timeless marriage of stone and wood, plaster and thatch, was too near perfection for me to wish to break away. The balance of golden buildings and green field, tree and rock, water and sky made the impatience retreat and my heart begin to sing. I wanted it, all of it: not just the house—I could have bought half a dozen sixteenth-century houses if I wished—but everything the house was, had been, would be. My mother’s family had migrated to England in the last century; my father’s people were rootless Californians; everything I owned that had been in my family for longer than two generations could be packed into a small travelling case.

Of course, for all I knew, Alistair’s people (those who were not Hughenforts) could have come here as recently as my own. But I thought not. The way he had moved in the house, his manner of speech to the two servants, evoked a sense of bone-deep kin with house and land. In Palestine, the man had been edgy and aggressive; here his testiness was gentled by the landscape.

Movement caught my eye in the formal garden behind the house: a black-and-white cat, picking its way through the wet grass, heading to the stables to hunt its breakfast. Down the valley, a cow complained; in the yard, a cock crew; on my hill, I sat, spellbound.

Had the house been more deliberately planned, if there had been the faintest air of artifice about the view, the perfection would have been cloying. As it was, the house and its out-buildings were uneven enough, the materials sufficiently varied to make it apparent that the man-made objects had grown up as organically as the trees. Badger Old Place, the Debrett’s listing had called it—and indeed, it even resembled the animal: low to the earth, shaggy and somewhat unkempt, its exterior giving little hint of the power and potential ferocity sheltering within.

I envied Alistair Hughenfort his home. I badly wanted to know what force had wrenched him away from it. I wished I could reconcile the two sides of the man. But above all, I wished that I had paused before coming out here to take a cup of tea.

Then, as if the universe had heard my string of desires and chosen to grant me at least one, a figure emerged from the house, and near-perfection shimmered into absolute: The figure carried a tray, and what is more, the tray was coming in my direction.

The bearer, I realised, was neither servant nor husband, but host. Alistair negotiated the stream via a series of rocks I had not noticed, scorning the shaky bridge, and strolled easily up the rise, the silver tray balanced on the fingers of one hand as if he were a waiter in a crowded café, a waiter dressed in a knit jumper of shades which would make a peacock proud.

He nodded as he drew near, but placed the tray on the bench beside me without a word. He then stepped bac

k and turned to face the house, looking wan, but rested.

“Good morning,” I said.

“Mrs Algernon was about to send a tray up. I told her I would take it. I did not tell her you were not in the house, so it will be cold.”

It was cool, but welcome. I poured and sipped; he stood and looked over his home, then pulled off his cloth cap and slapped it against his knee. I remembered clearly that of the two, Mahmoud had been the dour, rocklike one, Ali the volatile, always itching for action.

“The last time you brought me a cup of tea,” I told him, “was the morning before we reached Acre.”

“That was Mahmoud,” he responded automatically, without stopping to think. I had known it was Mahmoud; I merely wanted to hear him say his cousin’s name. “Marsh,” he corrected himself.

“It was Palestine, so I should say that ‘Mahmoud’ is correct.” I sipped my drink, wondering what had brought him up here.

“You and Holmes,” he began abruptly, “you were good at what you did. Mah—my cousin was impressed. He is not impressed by many. He may listen to you.”

“What are we to tell him?”

“He must leave this place. He no longer belongs here. It is laying its golden ropes around him, and choking him to death.” He glanced down to judge my reaction to this flight of fancy. When the side of my face told him nothing, he went on. “He thinks it a task required of him by his ancestors. A noble service. A sacrifice. It is not, I tell him, but his ears are deaf.” Stress had, I was interested to hear, brought the Arabic rhythm back into his speech.

“If your cousin has decided that family responsibilities require him to remain in this country, I can’t imagine that anything Holmes or I have to say will dissuade him.”

“Not say—but no, it is no good for me to tell you. You must see for yourselves, listen to him, draw your own conclusions.”

“Very well,” I told him. Then, since clearly he was not about to explain himself further, I changed the subject. “Where does the house name come from?”

“Not its appearance, if that is your question. You saw the boar’s head in the Hall? My ancestor who laid the foundations was hunting boar one afternoon in the year 1243 when the animal turned on him, and caught him unprepared. The tusks you saw on the head are real,” he added, “although the fur has been patched over the years. The animal would have gutted him in seconds, but for a badger’s den that gave way beneath the weight of the boar as it pivoted. That moment’s delay allowed Sir Guy de Hasard to set his spear and catch the charge. The boar died, Sir Guy lived, and the house he’d planned to build was moved half a mile up the valley to leave the badger in peace. There’s still a den there, in that copse you can just see over the hill.”

“Your people have lived here since 1243?”

“The first Badger Place was built shortly after that, although I should say the family had been here more or less forever. Seven generations of my ancestors have been born in the bed where now I sleep. I myself was born there. Half of them have died in that same bed. My people lived right here when the Domesday Book was compiled, not under the name Hughenfort—that came in by marriage during the last century—but the same family. Generation after generation farmed the land, reared their children, served the king, came home from the wars, and died in the bed where they were born.”

He seemed suddenly to notice the ever-so-faint air of wistfulness in his answer and the intensity of his gaze, because he blinked, then turned to me and added unexpectedly, “My sister’s son lives in the next valley. He farms this land; he will inherit it. He will move into the house, and die in that bed an old and happy man.”

“While Mrs Algernon’s pot of soup simmers away on the back of the stove.”

He granted me a quick smile, which made years fall away from him. “That I do not know. The old ways are disappearing. I have been away for twenty years, and the only thing I recognise is the land. The old order is gone. My nephew will not have a Mrs Algernon in his life.” He gave a last glance at his ancestral home, black and white and golden in the sun, then slapped the soft cap against his leg again and tugged it cautiously over his bandaged head. “However, if we don’t present ourselves to be fed, I may not have a Mrs Algernon for long, either.”

He gathered up the tray and led the way down the hill. I followed, thoughtful. Had he merely come to fetch me? Or to tell me that he trusted in the skills of the partnership Holmes and Russell? Or—odd thought—had he seen me sitting on the hilltop bench and been struck by a sudden desire for companionship?

Mahmoud—Marsh—at Justice Hall, Alistair here; it could not, I reflected, be an easy thing to be set apart from the day-to-day companion of two decades.

Breakfast was fortifying, the fuel of labourers. Afterwards, Holmes and Mrs Algernon bent over the scalp of an encouragingly irritable Alistair, pronounced themselves well pleased with the healing process, and replaced the bandage with a smaller plaster. Their patient stalked away, and Holmes and I went up to our rooms.

“We are to stay with Mah—with our old friend Marsh, then?”

“So it would appear. If nothing else, Alistair seems to have a minimum of servants at his disposal here.”

“He walked up the hill to tell me that Marsh was impressed by our skills, and that he might listen to us telling him to go back to Palestine.”

“So that is what Ali wants?”

“It sounded like it.”

“Should be a brief visit, then.”

So, our sojourn in the land of the gentry was to be a brief one. The thought cheered me considerably.

With the sun actually generating a trace of warmth, the motorcar’s bear-skin remained in hibernation. Alistair sat in the front beside Algernon, although there was none of the easy banter of the night before. Our host had also shed his colourful pull-over, although around his neck was draped a brilliant purple scarf with lemon-yellow fringes, topping the handsome grey suit he wore beneath a trim alpaca overcoat. Both of the latter garments were considerably newer in cut than the formal garb he’d worn to Sussex. On his head was an equally stylish soft felt hat, although he did not appear to have bothered having new shoes made during the four months he’d been in the country. His cheeks were smooth, his hair combed over the plaster, and from where I sat I could see his right leg jogging continuously up and down, the body’s attempt to release the tension that clenched his jaw and held his shoulders rigid. When threatened in Palestine, Ali had generally responded with a drawn knife; I couldn’t help speculating what the country house equivalent might be. Cutting insults at forty paces? Charades to the death?

We moved along the unmetalled road in the glorious autumnal morning, keeping straight when we reached the sign-post of the night before. “Justice Hall” was an interesting name for a ducal seat, I thought, and made a mental note to ask for an explanation.

The roads improved as we went on. Soon we were running alongside a stone wall far too high to see or even climb over; it went for what seemed like miles, high, secure, and blank. I was beginning to wonder if we were circling the estate rather than following one side when Algernon slowed and the wall dropped away towards a gate.

This was a very grand gate indeed, ornately worked iron hanging from twin stone pillars on which coats of arms melted into obscurity and atop which unidentifiable creatures perched. There was a snug, tidy lodge house at one side, from which a boy of about twelve scrambled, pulling on a cap as he ran, to throw himself hard against the weight of all that iron to get it open. He came to attention as we drove past, tugging briefly at his cap brim. Alistair raised a hand to him, but Algernon said loudly, “Thank you, young Tom,” receiving a gap-toothed grin in return.

The wide, straight drive that rose gently from the gate was flanked by fifty feet of close-cropped lawn on either side, behind which stood twin walls of vegetation—huge rhododendrons, for the most part; the entrance drive would be a pageant come spring. Taller trees, most of them deciduous, grew above the shrubs, to protect them from t

he summer sun.

We travelled steadily towards an open summit; as we neared the top, Alistair instructed Algernon, “Stop for a moment when we’ve cleared the hill.”

Obediently, the driver slowed, timing it so that as we reached the highest point we were nearly at a stop already. The bonnet tipped a fraction, and then Algy set the brake and turned off the engine.

Alistair climbed out; Holmes and I did not hesitate to join him at the front of the car. The view was, quite simply and literally, stunning.

As far as the eye could see, Paradise as a cultivated garden. A vast sweep of greensward, undulating with delicate dips and rises, dropping to the long curve of a lake with a glorious jet of fountain spouting to the heavens, the whole set with centuries-old trees as a ring is set with diamonds. It was far too perfect to be natural, but so achingly lovely that the eye did not care.

“One can say this for Capability Brown,” Holmes drawled. “He knew how to think on a grand scale.”

“Mostly Humphry Repton, actually,” Alistair told him. “Not that it matters, except down near the water.”

But the house; oh, the house.

I was, truth to tell, quite set to detest the place. Whatever its age, no matter its architectural or historical importance, Justice Hall was keeping Mahmoud Hazr from his rightful and chosen place in the world. No pile of stones or family tree justified the disruption of a man’s life—of the lives of two men. Two good, righteous, valuable men who had been happy doing hard and important work, until a brother had died and a title descended on one. I had no illusions that anything Holmes and I could say might prise Mahmoud from his perceived duty, but I had come here intending to try my damnedest.

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

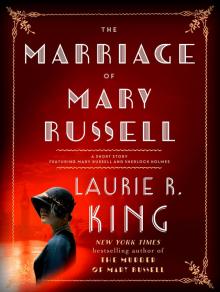

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

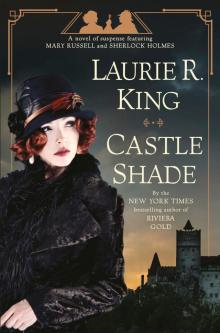

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

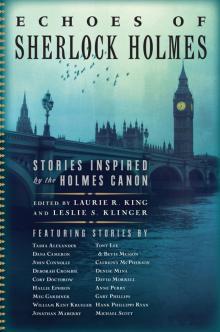

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1