- Home

- Laurie R. King

Night Work km-4 Page 5

Night Work km-4 Read online

Page 5

So no, Kate was not jealous—or rather, she was honest. Jealous, yes, a little. But hell, if Roz Hall had asked her to bed, she’d probably have gone too.

Roz had not asked. Instead, when Kate had been injured during a case the previous winter, while Lee and Jon were both away, it was Roz’s concerned face Kate saw from her hospital bed, Roz’s red Jeep that drove her home at her release, and Roz’s longtime partner, Maj, who brought Kate food and comfort and just the right amount of companionship to keep her going. The two women were now family, closer to Kate than any of her blood relatives, and if Kate sometimes felt like a poor relation bobbing in the wake of a glamorous star, well, Roz had a way of making one feel that even poor relations were good things to be. After all, even presidents had blue-collar cousins.

Kate relaxed back against the soft sofa pillows, looking with affection at their guests. The talk had circled back to Mina and her seven-weeks-to-go sister-to-be, and half of her attention was on that. The other half drifted back to the Larsen murder, which seemed to be progressing on as straightforward a path as investigations ever did, but which nonetheless niggled at the back of her mind.

One of the things she had to find out, she decided, was what Larsen was doing in the Presidio parklands at that hour. Emily had not been able to think of anything that would have taken her husband there, and neither could Kate. A trap, maybe. Perhaps Crime Scene’ll come up with something in the Larsen house, she thought, and then woke to the fact that Roz was talking to her.

“Sorry,” she said, sitting upright to demonstrate her attentiveness. “I was miles away.”

“Difficult case?”

“Puzzling,” she conceded. Good manners required that she answer, but she could hardly go into the details of an active case. This was a problem she’d faced countless times over the years, however, and she had become skilled at the diversionary side-step in conversation. “I was thinking about this interview I had today with an abused woman. I just… it continually amazes me, what women will put up with for the sake of security.”

“Oh, that’s not fair,” Lee protested. “It’s not even true, to call it security. They often live in a constant state of fear.”

“So why do it? Because the known, however awful, is better than the great unknown?”

“Sometimes it is,” Roz broke in. “Especially when there are children, and no other family or friend to lean on. We’re a terribly solitary culture, you know. It’s not easy to find a support network in modern society, especially if you’re a woman who already feels humiliated by being someone’s punching bag. Self-respect is a luxury, and sometimes all these women can afford is pride, that they won’t admit failure.”

There was nothing in Roz’s face or voice to show that her words were anything but general; nonetheless, Kate eyed her with the uneasy sensation that there was some underlying message there for her alone. Roz’s next words confirmed it, and the evenness of her gaze.

“We all do this, to some degree, even if we’re not in an actively abusive relationship. We let ourselves be shoved into a corner, humiliated, used, and abandoned, and then when our partner turns back to us, in the joy of reunion we forgive.”

A memory swept into the room, so vivid in the space between Roz and Kate that it seemed to quiver visibly in the air.

It was a scene from the previous December, a few days after Kate’s release from the hospital to her cold and empty house. The morning had been taken up by one of her blinding headaches, legacy of a suspect’s eighteen-inch length of galvanized pipe. In the afternoon Kate had wakened from a drugged sleep, stumbled into the bedroom she and Lee had shared until Lee’s cruel and abrupt departure in August, and at the sight of the antique Wedding Rings patchwork quilt on the bed, she was seized by a rage so powerful it felt as if the spasm of migraine had finally invaded her mind.

She had not heard Roz letting herself in downstairs. She only became aware of her visitor when Roz was standing in the doorway, looking down at Kate where she sat on the floor, surrounded by the ten thousand shreds of faded cotton fabric and cotton batting that had been a quilt. Kate paused in her methodical and heavily symbolic destruction, saw in Roz’s face the full, calm knowledge of precisely what she was doing, and then erupted into tears, wracked by hard, painful sobs of fury and despair that were wrenched out of her abandonment and betrayal. Her headache reawoke and her eyes and throat were seared raw, but Roz held her and rocked her, more maternal and comforting than Kate would have imagined possible.

They had never spoken of it after that day, and Kate had occasionally wondered if Roz had told Lee, but at that moment, sitting in front of the fireplace with their coffee cups and their partners, Kate saw that Roz had said nothing to anyone about the depths of the despair that Lee’s leaving had visited on Kate. The sanctity of confession held, Roz’s eyes said, even for the pastor of a church without confessionals.

The memory, and the knowledge, flashed between them in the blink of an eye, an instant of complete communication that Kate had only ever known in the intimacy of an interrogation room, with a suspect on the edge of a very different sort of confession, or a bare handful of times with Lee. The memory puffed away and vanished, leaving Kate disconcerted, and depressingly aware that she was even more deeply indebted to Roz Hall than she had thought. She cleared her throat and reached back urgently for the tag end of the conversation they had been having.

“Forgive, sure,” she said. “But only so many times. These women, though, their forgiveness is pathological.”

Roz, still holding Kate’s eyes, nodded. “True. We are told to turn the other cheek in offering up our humility. We are not told to go on doing it indefinitely.”

“Or told to put a club into the hand that slaps us. There was this picture on the wall in one of the law offices, that showed a woman who’d had the crap beaten out of her, all black-and-blue and bandages, with the caption ‘But he loves me.” And you know, that’s exactly what the woman I was interviewing said, that the husband who’d been beating her for years and years was, I quote, “a good man’ who ‘loved us.” “ To Kate’s relief, Roz’s attention finally shifted.

“Love and rage,” Roz said thoughtfully. “They’re never that far apart, are they?”

This time, the brief reaction that shot through the room reached across the other diagonal: Lee and Maj both twitched, almost imperceptibly. A faintly ironic smile played briefly over Maj’s mouth before she wiped it away with a sip of her tea. Roz did not seem to notice anything, since she was now exploring an idea, a frown of thought between her eyebrows.

“That’s more or less what I’ve been doing in the thesis, looking at how in the Old Testament you see God as creator, nurturer, loving mother/father, and protector, yet also as judge and executioner, enraged at a wayward people and on the verge of destroying them completely.”

“Is it linked with the male/female imagery?” Lee asked her. Anyone who had been in Roz’s circle for more than a few days was made quickly aware of the Bible’s references to God’s femininity, the metaphors of childbirth and child rearing used to describe the Divine. The God known by Roz Hall both begot and gave birth, and Roz was not about to let anyone forget it. Even a certain homicide cop was familiar with that bit of theological interpretation.

“You’d think it would be, wouldn’t you?” Roz answered. “That in the passages referring to childbirth, God would be the loving mother, and in the God-the-father passages there would be judgment and wrath, but it’s not that simple. The two go hand in hand, just like the ancient Near Eastern goddess figures that switch between love and destruction at the drop of a hat. It may have something to do with agricultural fertility— that floods bring destruction and life at the same time, that fruit and grain ripen at a time of year that appears dead.”

They had gone far indeed from the subject of Emily Larsen, and all three of Roz’s unwilling audience cast around desperately for a diversion. Kate got there first.

“Still, I doubt that some

one like the woman I talked to today thinks of her husband as particularly divine. I think she’s too busy praying that he comes home in a good mood.”

It took Roz precisely two seconds to pause, blink, and make the shift from academic theoretician to pastoral counselor.

“Most of what I do in the group sessions is to drive home a dose of hard reality. I teach these women to say to themselves, ”My partner won’t change; it’s up to me.“ But I make sure they add, ”I have the support of my friends.“ ”

“Sounds like a mantra,” Lee said. “ ‘Every day in every way I’m getting freer and freer.” “

“Change your mind, change your life,” Roz agreed.

“If their husbands don’t catch up with them first,” Kate added darkly.

“There is that. And sometimes it’s so obvious they’re in danger, and they’re so oblivious, it’s all I can do not to take them by the collar and try and shake some sense into them.”

“You might be talking about Emily Larsen. I don’t suppose you’ve met a woman by that name at one of the shelters?”

Roz reflected for a moment. “There is a client named Emily in the one on West Small Street, but I don’t know what her last name is. We don’t use surnames in group sessions, or even in one-to-one counseling, so unless I’m involved with the paperwork, I usually don’t know their full names.”

“Her husband’s name was James, or Jimmy.”

“Was?”

“He’s dead.”

“Oh dear. That’s her. Black hair, glasses? She’ll be crushed, I’m afraid. She must have said his name fifty times during the session on Monday. Classic. I must go see her.”

“So you were at the shelter on Monday night?” Kate asked, trying to sound casual but aware of Al Hawkin’s sarcasm, and of Lee at her side.

“Leading a group therapy session. I’m there two or three times a week. The director’s a good friend.”

Half the city was Roz’s good friend. “How late—I’m sorry, Roz, it’s not very nice to ask you for dinner and then question you, but the woman’s husband was killed on Monday and it would save me having to hunt you down tomorrow to ask these questions. Can you tell me how late you were there?”

“I don’t know. Fairly late.”

“You got home at five after twelve,” Maj offered with mild disapproval.

“So I must have left the shelter about eleven-forty-five. The group session is from seven until about nine, and I stayed on to talk with Emily for maybe an hour before I left. Are you looking for an alibi?”

“Oh, Emily Larsen’s clear,” Kate told her—the literal truth, if skipping over some of the details. “We’re just looking for information, filling in the gaps, you know? Was she with you the whole time, then?”

“Not the whole time, no. When the session ended I had to talk with someone who was needing advice fairly urgently for a friend, a neighbor I think, who’s in an ugly situation—the neighbor’s an Indian girl, from India, I mean, barely more than a child by the sound of it, who was brought here in an arranged marriage—can you believe it? In San Francisco in this day and age? The child’s in-laws disapprove of her, and it’s beginning to escalate into physical abuse. The woman who came to me is worried, and I had to talk to her about the girl’s options, whether or not to just call the police, or to turn it over to Child Protective Services, who would involve the school district and a dozen other agencies. Anyway, I was with her for about half an hour, forty-five minutes, and then I went back to Emily.”

“So you were inside the whole time?” Kate asked, her voice as casual as if she were asking for the cream. Lee was not fooled, however, and shot her partner a hard look. Roz looked slightly uncomfortable, which was a hidden satisfaction to Kate, but she answered readily.

“No, not inside. We were outside in Amanda’s car.”

“Did you see anybody leave after the group session?”

Roz saw where the questions were going, and relaxed a degree. “A couple of people left, sure. Carla Lomax and her secretary, Phoebe, and a woman named Nikki. There might’ve been someone else, I can’t remember.”

“If you think of anyone, let me know. What about Carla Lomax, Emily’s lawyer? Do you know her? I gather she got Emily into the shelter in the first place.”

“We’ve worked together from time to time, but I can’t say I know Carla well. Good woman, very committed.”

Lee sat forward on the sofa and firmly nudged the conversation away from Kate’s professional interest in Emily and James Larsen. “What about that Indian girl? Is there anything you can do about her, unless she’s underage? The Indian community tends to be pretty closed to outsiders, doesn’t it?”

“Even more than the Russians, and I thought they were tight-lipped. You’re right, I can’t do anything direct, but there are people who can, and it’s just a matter of digging them out and tightening the screws.” She looked, for a moment, oddly fatigued, and her laugh was a bitter one, full of long experience of hopeless causes. “You wouldn’t believe how Machiavellian I can be if I have to. I listen to the right-wingers and then to the left, and I agree with all the extremists to their faces. I eat shit and ask sweetly for the recipe. I even learned how to bat my eyelashes at men, if you can imagine that.”

Kate glanced at Lee, to see what she was making of this, and saw a look of wary compassion on her lover’s face.

“And when she has eaten the shit,” Maj added in her slight, precise Scandinavian accent, “she comes home and breaks the furniture in a rage.”

“I do not!” Roz protested.

“Only once,” Maj allowed. “And I hated that chair anyway.”

“God, it must be exhausting,” Lee broke in. “Conflict resolution’s the hardest job in the world.”

“Isn’t it just?” Roz agreed. “You know, more than once when I’ve been sitting in a room with two people, each of whom thinks the other is a monster of depravity, I’ve found myself fantasizing about just cracking their skulls together, or locking the two of them up together until they promised to treat each other like human beings. They wouldn’t even have to agree with each other, just be polite and listen.”

Kate was reminded of the notice that she had read while she was sitting with the phone under her chin, waiting for Carla Lomax to come on the line. “Have any of you seen that flyer somebody’s been putting up on phone poles, suggesting that mothers should be required to insert a poison capsule under their sons’ skin at birth?”

“What?” Lee said, shocked.

“Yeah. The idea is, if the boy gets out of hand as an adult, society could just trigger the capsule and deal with him. Shut him down.” It was not, she realized belatedly, a topic a pregnant woman might be eager to discuss. Maj didn’t wince, exactly, but she seemed to retreat slightly into herself. Lee, of course, caught it and moved to soothe, but before she could knock Kate’s comment out of the air with a remark about the weather, Roz picked up on it.

“God, people are nuts,” she was saying. “We have this friend whose lover left her because the baby she was carrying turned out to be a boy, and she couldn’t take the conflict of raising a male child. I mean, men are half the human race. Who better to change the way they do things than lesbian mothers?”

“Nurture overcoming nature,” Lee said in agreement.

“The irony is painful, isn’t it?” Roz went on. “In developing countries they’re aborting thousands of fetuses every month because they’re girls and amnio followed by abortion is cheaper than coming up with a dowry, while at the same time in the West women are aborting babies because they’re males and they don’t want to deal with the problem of raising a male feminist. I mean, I’m all for the right to choose, but not over something petty. It’s… obscene.”

“Abortion has to be chosen with care,” Lee agreed, uneasily going along with a topic she was interested in but keeping one eye on Maj. “There are always consequences. Sometimes it takes years for them to manifest, but they’re there, and it’s irres

ponsible to pretend they’re not.”

“You know,” Maj said, going back to Kate’s original remark to show that it did not bother her fragile, hormonally ravaged pregnant self, “the whole anti-male paranoia just gets to me. I wouldn’t mind if this baby were a boy. You can’t just say that men are violent, period. It isn’t their sex that condemns men to brutality, it’s their history.”

“It’s not men I mind,” Lee noted. “It’s mankind I can’t stand.”

“Hey,” Kate objected, straight-faced. “Some of my best friends are males.”

Their laughter was interrupted by the doorbell, and Kate went to let in Mina, being dropped off by the neighboring friend’s mother. While the mothers chatted briefly, Lee got out an antique globe puzzle that had belonged to a great-aunt and showed Mina how it worked. When the mother left and with Mina in the room, the evening’s talk slid on to less loaded matters than abortions and the iniquity of men.

Before long, however, Mina abandoned her attempt at reassembling the various layers of the globe. She wandered over to sit on the sofa beside Maj, who put out an arm and drew the child in to her. Almost instantly, Mina’s eyelids began to droop, and her thumb went briefly into her mouth before she remembered that she was too old to suck her thumb.

“You tired, sweet thing?” Maj asked her. Mina’s head nodded against her adoptive mother’s shoulder. “Me too,” Maj said. “Can you help your fatty ma up?” With Mina pulling (and Roz behind her adding an affectionate but only half-joking shove), Maj maneuvered herself upright and waddled off to use the toilet for the fourth time that evening. Roz bent down and picked up Mina, who snuggled happily into her other mother’s arms and fitted the top of her head into the hollow of Roz’s chin. Roz’s arms went around the child with fierce affection, and by the time Maj came out of the bathroom, Mina’s legs were limp in sleep. Lee watched the family leave with envy in her eyes.

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

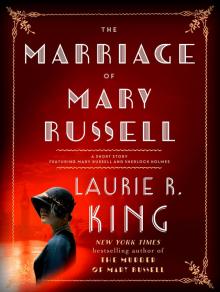

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

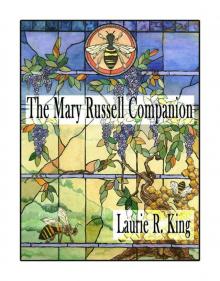

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

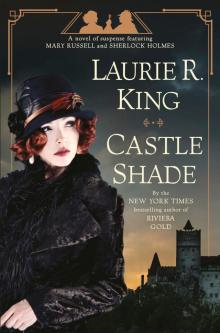

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1