- Home

- Laurie R. King

The Language of Bees Page 6

The Language of Bees Read online

Page 6

“Until she disappeared.” Holmes sat back, one finger resting across his lips; I sat forward. “This was Friday. Three days ago. I'd been up late Thursday, working, and I fell asleep in the studio—I keep a bed there, so I don't disturb the household with my comings and goings. I slept until noon, then went home. The maid, Sally, told me that Yolanda had gone out first thing that morning with a packed valise, saying she wasn't sure when she would return.”

“Had she received a letter? A telegram?”

“Not that Sally knew, and the only time she'd been away from the house was when she went to the greengrocer's Thursday afternoon. I was more puzzled than alarmed—Yolanda does this sometimes, goes off for a day or two. She calls them her ‘religious adventures.’ Still, she always tells me when she's going to be away, and with her recent uneasiness in mind, I found myself distracted. Twice I left my painting to walk home and see if she had come back. She hadn't.

“So on Saturday I woke up early, and when there was still no sign of her, I sent Sally out to do the round of Yolanda's friends, to see if any of them knew where she was. While she was doing that, I went around Yolanda's favourite churches and temples and the like, but no-one had seen her in days. I didn't know what else to do, so I went back to the studio, but I couldn't settle to work.”

“You didn't wish to notify the police?”

“No. Not until, well, considerably longer. And then when I returned to the house around tea-time, Sally gave me an envelope she'd found under my pillow, where Yolanda had put it before she left. It could have sat there for days, if I'd continued to sleep at the studio, but when Sally'd come in, she couldn't decide what to do with herself, not knowing if we were in for dinner and all, so she'd decided to strip the beds.”

Holmes made a small gesture of impatience with his finger, and Damian abandoned the question of out-of-sorts maidservants.

“Anyway, this is what she found.”

Damian reached around for his jacket and fished out not one, but two envelopes. He half-rose to hand the light blue one to Holmes. For a moment, the slip of blue linked two near-identical hands, then Holmes' long fingers were pulling at the contents, tipping the page so that I, too, could read the words. They were written in a precise, bold hand:

Dearest D,

I am going away for awhile, on what I suppose is one of my religious adventures. This time I've taken E with me. I must ask you to be patient, although I know that you always are.

Your loving Y

P.S. I don't think I've told you in awhile, that you are the best thing that could have happened to me and to E.

“Who is—” Holmes started, then cut off as Damian stood up and held out the second envelope. His clenched jaws declared that here, at last, was what he had been working towards: There was resentment in his face, and embarrassment—perhaps even shame—but also determination.

Holmes took the envelope; Damian retreated, not to his chair, but to the low wall at the back of the terrace, where we could only see his outline and the glow of his cigarette. Holmes' fingers pushed back the flap, and eased out a photograph.

It was a snapshot, showing three people. Damian Adler stood in the back, wearing a dark, formal frock coat and high collar: From his overly dignified expression, the costume was a joke. In front of him, the top of her head well below his shoulders, stood a tiny Oriental woman. She wore Western dress, looking more comfortable in it than many photographs of Orientals I had seen. Her ankles were shapely under a slightly out-of-date dress, her glossy black hair was bobbed; her dark eyes sparkled at the camera with the same sense of humour as his.

It was the third person in the photograph that made Holmes go very still and caused my breath to catch: a child around three years old, held in the woman's arms. Damian's right hand was on the woman's shoulder, but his left arm circled them both; his hand looked massive beside the infant torso. The child's features had blurred slightly as she swivelled to crane up at Damian, but the glossy hair was every bit as black as the mother's.

“My wife, Yolanda,” Damian said into the pregnant silence—and there seemed no trace of embarrassment in his voice, only affection and worry. “And our daughter, Estelle.”

He came off of the wall, to look over Holmes' shoulder at the photograph.

“Estelle is missing, too,” he said. “I need …” He cleared his throat, and frowned at the picture in his father's hand. “I need you to help me find them.”

His embarrassment, I saw at last, was not over having married a woman of Shanghai, nor even that his wife had a dubious past. His shame was because he had been forced to come to Holmes for help.

The Father (2): Some men remember their childhood

among women. These few may reach back and find the

shadows to their light, the receiving to their giving,

and bring the worlds together.

These men are called saints, or gods.

Testimony, I:3

I LEFT HOLMES AND DAMIAN TO THEIR DISCUSSION A short time later, both through tiredness—we were, after all, just off an Atlantic crossing, and I never sleep well on the open seas—and cowardice: I did not wish to be there when Holmes suggested to his already estranged son that hunting through London for an eccentric, free-spirited daughter-in-law might not be the most productive use of his time.

Also, I needed some time alone to grapple with the idea of Holmes—of myself!—as a grandparent.

Lulu had unpacked my valise, although she knew me well enough to leave the trunks untouched, so I had hair-brush and night things to hand. I ran a hot bath, and felt my muscles relax for the first time in many days.

As I walked down the hallway to the bedroom, I heard that the men had moved inside, and one of them had considerately shut the sitting room door so as not to disturb me. The lack of raised voices indicated an amicable discussion, which suggested that Holmes had very sensibly agreed to assist his son. I climbed into bed, leaving the curtains open to the light of the moon, three nights from full.

From where I lay, I could see the grey glow of the treetops in the walled garden, and beyond them the ghostly outlines of the Downs. Thanks to the extraordinary appearance of Damian Adler on our terrace, I had missed the sunset completely.

I was grateful beyond words that he had re-entered our lives, and not only because of the hole that their uncomfortable meeting had left in Holmes. The world is large, when a man wishes to disappear, and the tantalising possibility that he was still out there had gnawed silently at us both.

I was especially pleased that Damian had grown into a man with weight to his personality—it would have been hard, had he turned out charming (a shallow quality, charm, designed to deceive the unwary) or dull. Instead, he was intelligent (which one would expect) and madly egotistical (marching in and laying his life and problems before us, without so much as a by-your-leave—but again, what might one expect of the offspring of two divas?) and he possessed that animal magnetism born of intensity.

It was difficult, with the artistic personality in general and the Bohemian way of life in particular, to know how much of their eccentricity was cultivated and how much was true imbalance. Damian had been hiding a lot, both in fact and in emotion. I had sensed deceit woven throughout the fabric of his story, everywhere but in his declared love for wife and child. However, subterfuge was perhaps understandable in a man coming to ask a favour of the father he barely knew, the eminent and absent father whose hand he had refused to shake, five years before.

The complexity of the man was both a comfort and a concern. I could only hope that, now he was here, Holmes would take considerable care not to drive him away—but, no, I decided, there would be little chance of that, not after he had held that photograph of Damian's family. I looked forward to meeting Yolanda Adler, wherever she had taken herself off to.

If nothing else, I thought as I pulled up the bed-clothes, a renowned Surrealist with a missing Chinese wife and small daughter promised to fill nicely the anticipated tedium of

Holmes' return.

I woke many hours later with birdsong and the first rays of sun coming through the open window.

The house was still: Lulu would not arrive until ten, and the two men had talked until the small hours. Holmes had not come to bed, but that was a common enough occurrence when he was up late and did not wish to disturb me.

However, he was not in the small bedroom next door, nor on the divan in his laboratory. He was not in the sitting room, or on the terrace, or in the kitchen, and there was no sign that he had made coffee, which he did whenever he was up and out before the rest of the house.

I walked down to the door of the guest suite, where Lulu would have installed Damian. It was closed. I pressed my ear to the wood, hoping it wouldn't suddenly open, dropping me at my step-son's feet, but I could hear no sound from within. I frowned in indecision. Perhaps they had talked all night, after which Holmes had been struck by the desire to see his devastated hive.

Without coffee?

I tightened the belt on my dressing gown and reached for the knob. It ticked slightly when the tongue slid back, but the hinges opened in silence. I put my head around the door.

Nothing. No sleeping Damian, no foreign hair-brush or pocket change on the dressing table, no reading matter on the bed-side table, no carpet slippers tucked beneath the wardrobe. The bed had not been slept in; the window was shut. Stepping inside, I confirmed that the room was bare of his possessions, although clearly he had been here: He'd left a few crumpled bits in the waste-basket, along with a clump of hair from a hair-brush.

Upstairs, a quick search revealed that Holmes had not packed a valise for himself—but then, a man who maintained half a dozen bolt-holes in London did not need to carry with him a change of shirt and a tooth-brush.

Especially if doing so risked waking me with the creaks of the old wooden staircase.

I went back through all the rooms in the house, ending in the sitting room, where ashes and the level in the cognac decanter told of a lengthy session. There was no note to suggest when or why they had left, or for how long.

I sighed, and went to the kitchen to make coffee.

Holmes' unplanned and unexplained absence was by no means sinister, or even suggestive. We were hardly the free-love Bohemians of Damian's circle, but neither did we live in one another's pockets, and often went our separate ways. If Holmes had gone off with his son in search of a wayward woman and child, he was not required to take me with him, or even to ask my permission.

He might, however, have written me a note. Even Damian's wife had done as much.

I drank my coffee on the terrace as the world awoke, and ate a breakfast of toast and fresh peaches. When Lulu came, chatting and curious, I retreated upstairs, put on some old, soft clothing that had once belonged to my father, and began the lengthy task of disassembling my travelling trunks.

I emptied one trunk, reducing it to piles for repair, storage, and new possessions. As I was sorting through the odds and ends of the past year—embroidered Kashmiri shawl from India, carved ivory chopstick from California, tiny figurine from Japan—I came upon an object brought from California in a transfer of authority, as it were: the mezuzah my mother had put on our front door there, which a friend had removed at her death and kept safe for my return.

I looked up at a tap at the half-open door.

“Good morning, Lulu,” I said. “What can I do for you?”

“Mr Adler, ma'am. Is he coming back? It's just that his room looks empty, and if he's not going to be needing it—”

“No, I think he's left us for the time being.”

“That's all right, then, I thought he'd finished, and with Mrs Hudson coming home on the week-end and all I wanted—”

“That's fine, Lulu.”

“Are you nearly finished in here, because I could help if you—”

Lulu was an implacable force of nature; as Mrs Hudson had once remarked, if a person waited for Lulu to finish a sentence, the spiders would make webs on her hat. I abandoned the field of battle, and retreated downstairs to start in on the mail.

By noon I had written an answer to a letter from my old Oxford friend Veronica, admiring the photograph she had sent me of her infant son, and responded to a list of questions from my San Francisco lawyers concerning my property there. Another letter from an Oxford colleague was pinned to a paper he was due to present on the Filioque Clause, for which he wanted my comments. I dutifully waded into his detailed exegesis of this Fourth Century addendum to the Nicene Creed, but found the technical minutiae of the Latin trying and eventually bogged down in his attempted unravelling of the convoluted phraseology of Cyril of Alexandria. I let the manuscript fall shut, scribbled him a note suggesting that he have it looked over by someone whose expertise lay in the Greek rather than the Hebrew Testament, and stood up: I needed air, and exercise.

But first, I hunted down a book I'd thought of on Holmes' shelves, then followed thumps and rustles to their source in the upstairs hallway. Lulu looked up as my presence at the head of the stairs caught her eye.

“I'm going for a walk,” I told her. “Don't bother to set out any luncheon, I shouldn't think either of them will be back. And when you've finished here, why don't you take off the rest of the day?”

“Are you certain, ma'am? Because I really don't mind—”

“I'll see you tomorrow, Lulu.”

“Thank you, ma'am, and I'll make sure to lock up when I go, like you and Mr Holmes—”

I laced on a pair of lightweight boots I had not worn for the best part of a year, took a detour through the kitchen to raid the pantry for cheese, bread, and drink, and left the house.

I turned south and west, following the old paths and crossing the new roads towards where the Cuckmere valley opened to the sea. The tide was sufficiently out to make the small river loop lazily around the wash; three children were building a castle in the patch of sand that collected on the opposite bank. Even from this distance I could see the pink of their exposed shoulders, and I thought—the back of my neck well remembered—how sore they would be tonight, crying at the touch of bed-clothes on their inflamed skin.

Which image returned me to my thoughts before sleep the night before: the photograph, and the child. Her name was Estelle, Damian had told us, after the bright stars on the night she was born. An odd little girl, troubled by everyday things another child would not even notice—she would exhaust herself with tears over the sight of a feral cat in the rain, or a scratch on the leather of her mother's new shoes. But clever, reading already, chattering happily in three languages. She and her father were closer than might normally be the case, both because she was in and out of his studio all day, and because of Yolanda's periodic absences.

He wanted us to understand, Yolanda was not an irresponsible mother. The child was well looked after, and Yolanda never went away without ensuring Estelle's care. It was simply that she believed a child did best when the parents were satisfied with their lives, when their sense of excitement and exploration was allowed full expression. Self-sacrifice twisted a mother and damaged the child, Yolanda believed.

Or so Damian said.

Personally, I thought he seemed too willing to forgive his wife both her present whims and her past influences. Without meeting the woman, of course, I could not know, but the bare bones of the story could easily paint a far less romantic picture, beginning with the blunt fact that a young woman whose friends were prostitutes was not apt to be an innocent herself. And, running my mind back over Damian's tale, it occurred to me that he had taken great care to say nothing of what she had been doing between leaving the missionary school at eleven and being kicked onto the streets at sixteen.

Without a doubt, he had been besotted with her—even his gesture in the snapshot testified to that—but this was a man whose life's goal was to embrace light and dark, rationality and madness, obscenity and beauty.

One had to wonder if the affection was as powerfully mutual. One might as easily posit a

nother scenario: Desperate young woman meets wide-eyed foreigner with considerable talent and an air of breeding; young woman flirts with the young foreigner and engages his sympathy along with his passion: Young woman encourages the man's art, nudges him into financial solvency, and finds herself pregnant by him. Marriage follows, and a British passport, and soon she is in London, free to live as she pleases, far from the brutal streets of Shanghai.

Without meeting her, I could not know. But I wished Holmes had stuck around long enough for us to talk it over. I wanted to ask how he felt about having his son marry a former prostitute.

I left the path at the old lighthouse, to sit overlooking the Channel, and took from my pockets the cheese roll, the bottle of lemonade, and the slim blue book I had found in the library between a monograph on systems of zip fastening and an enormous tome on poisonous plants of the Brazilian rain-forest.

I ran my fingertips across the gold letters on the front cover: Practical Handbook of Bee Culture, the title read, and underneath: With some Observations upon the Segregation of the Queen.

I had read Holmes' book—which he, only half in jest, referred to as his magnum opus—years before, but I remembered little of it, and then mostly that, for a self-proclaimed handbook, there seemed little instruction, and nothing to explain why its author had retired from the life of a consulting detective at the age of forty-two in order to raise bees on the Sussex Downs. Now, nine years and a lifetime after I'd first encountered it, I opened it anew and commenced to read my husband's reflections on the bee. He opened, I saw, with a piece of Shakespeare, as I remembered, Henry V:

The honey-bees,

creatures that by a rule in nature teach

the act of order to a peopled kingdom…

Chief among the everyday miracles within the hive is that of how the first bee discovered the means by which watery nectar, vulnerable to spoilage, might be made to keep the hive not only through the winter, but through a score of winters. Can one conceive of an accidental discovery, a happenstance that arranged for the hive sisters to be arrayed en masse at the mouth of their hive, fanning their wings so vigorously and for so long that the nectar they had gathered evaporated in the draught, growing thick and imperishable? And yet if not an accident, we are left with two equally unsatisfactory explanations: a Creator's design, or a hive intelligence.

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

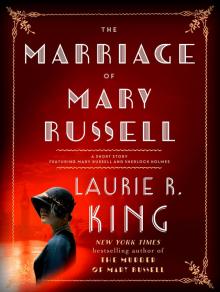

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

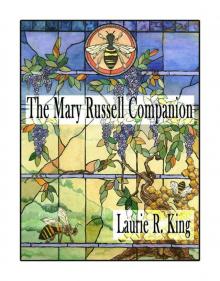

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

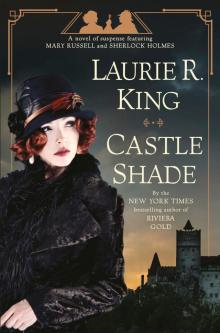

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1