- Home

- Laurie R. King

The Game Page 9

The Game Read online

Page 9

Wary, unwilling to relax his guard, the man minutely settled his lapels and suggested, “Memsahib, I would be honoured if you were to permit me to arrange for a man to bring to your room a selection for your approval. And of course the hotel will make a gift of them, by way of a small apology.”

I felt very small myself. When he had made his escape, I went to sit near Holmes.

“Very well, you were right. Why did I do that?”

“I don’t know, but every so-called European does. Do you wish to wait until you have your new shoes before we go out?”

“Oh, no. I’ll just pretend that leprous shoes are the latest French fashion.”

I could only hope that they would remind me not to lose control again. Perhaps it only happened once, and then one had it out of one’s system.

If only they weren’t all so friendly and agreeable as they drove a person mad.

And the beggars—my God! I had met beggars in Palestine, but nothing like these. Of course, there I had worn the dress of the natives, but here, in European clothing, the instant we set foot outside the hotel we were magnets for every diseased amputee, wild-eyed woman, and sore-riddled child in the vicinity. Unfortunately, the note that had been waiting for us on our arrival the night before had neglected to say anything about transport being provided, so Holmes had asked for a cab. What awaited us was powered by four legs rather than a piston engine, but we did not hesitate to leap in and urge the driver to be off. The tonga’s relative height and speed would afford us a degree of insulation from the beggars’ attentions.

Delhi, the Moghul capital that was currently in the process of being remade as a modern one, nonetheless more closely resembled Bombay than it did London. The streets through which we trotted looked as though someone had just that instant overturned an anthill—or rather, as if a light covering of earth had been swept away from a corpse writhing with maggots. Furious, pulsating activity, occasional wafts of nauseous stench, unlikely colours. And blood, in seemingly endless quantities, spattering the recess in which a blind beggar perched, forming a great scarlet fan on a whitewashed building past which a pair of oblivious officers strolled, reaching up a mud-brick wall towards the sleeping figure along its top (at any rate, I trusted he was merely sleeping). I was just turning to say something to my companion when a rickshaw puller hawked and spat out a gobbet of the same red colour that decorated every upright surface, at which point I realised that the substance was of a lesser consistency and not quite the crimson of fresh blood. This had to be betel, the mildly narcotic chew of the tropics. The marks were still revolting, but considerably less alarming.

We left the main thoroughfare and rose into an area both newer and cleaner, with fewer pedestrians and the occasional motorcar. We went half a mile without seeing a beggar. The high walls were iced with hunks of broken glass, each gate attended by a man with a rifle. The guards wore a variety of regional clothing and their turbans could have stocked a milliner’s shop, but each face held an identical look of suspicion as we clip-clopped past.

The gate before which our tonga stopped was no higher than its neighbours’, the guard no more nobly clad, but where some of the others had given the distinct impression that their guns were empty and for show, the stout Sikh here left one with no doubt that he would not hesitate to shoot down even a sahib, if it proved necessary. He watched us climb down from the horse cart, his only response a brief twist of the head (his eyes never left us) and an even briefer phrase grunted over his shoulder in the direction of the gate.

Before Holmes could dig into his pocket for the note we had received, the stout gate swung open. Inside it stood a slimmer, younger Sikh in beautifully laundered salwaar trousers and long, frock-like kameez, who bowed his snug sky-blue turban in greeting.

“You will please walk with me?” he suggested.

Chapter Seven

The garden within the gates was a place of Asiatic loveliness, a Paradise of birds and flowering trees, decorated by an old mali and his young assistant wielding watering cans, and a pale, cud-chewing bullock placidly waiting to be attached to the lawn mower. Brilliant potted flowers—rose, hibiscus, bougainvillea—marched the length of the drive, and near the house a fountain splashed and glittered. The rush and stink of the town was cut off as if by an invisible wall, and I felt my skin relax against my already-damp dress.

The bungalow was worthy of its grounds, simple and white, its verandah set with rattan chairs and tables, the entrance hall-way an expanse of linen-covered walls and gleaming dark flooring of teak or mahogany. The servant’s soft sandals made slight noise as we crossed to a doorway. He stood back to let us enter, said, “I will bring tea,” and left us.

The room was a light, open space looking out onto the garden. Its simple furniture was a far cry from the Victorian stuffiness, mounted animal heads, and heavy draperies that I had expected from a Raj household. The house’s silence seemed another carefully chosen furnishing of the room, its texture broken only by a rhythmic creak of machinery out-of-doors and the rise and fall of a voice from somewhere deeper in the house. It was a one-sided conversation—over the telephone, I decided, since it paused, resumed, and paused again. Tea was brought and poured, the servant departed without a sound, and I carried my cup over to examine the objects on the wall.

Near the door was a collection of framed photographs, groups of men with horses and dead animals such as one sees in the social pages of The Times. One photograph, placed centrally among the others, showed three men on horse-back: at the left side a dark-haired Englishman, and on the right a smaller man with a bandaged arm, whose face was half hidden by the shadow of his topee but whose blond moustache said he was European as well. Between them sat a darker-skinned man, hatless, aiming his black eyes at the shutter as if he owned it, with an expression beyond pride—more an amused patience with the antics of underlings. Out of focus on the ground before them were two mounds resembling small furry whales, with a scattering of dogs and turbanned beaters behind. At the bottom of the photograph were written the words “Kadir Cup, 1922.” Beside the photograph was one of identical size and frame, showing only the blond man and the native, except in this one, the darker face was tense about the jaw, as if a furious argument had broken off moments before. The black eyes flashed at the camera, the hand holding the reins was clenched tight. This one said “Kadir Cup, 1923.”

The other photographs were of similar occasions, several showing the blond man, although in most of them his face was at least half obscured by hat or hand. Beside one of them hung a plaited horsehair thong with a single claw nearly as long as my hand, which I thought might be from the tiger shown dead in the picture. Mounted above this shrine to the masculine arts were two spears, or rather, one long spear and the remains of a second, consisting of a broken head and about eighteen inches of shaft. The viciously sharp iron heads on each were stained, probably with dried blood.

I moved on to the more customary art-work on the next wall, and found it pleasingly light, almost feminine in its sensibilities. Half a dozen watercolour sketches of the Indian countryside alternated with ink drawings, crisp black lines on the white paper showing simple scenes of village life—a woman with a large jug balanced on her head, a man and bullock ploughing, a child and dog squatting beside each other to stare down a hole. The drawings especially were striking; I thought they would not look out of place among a display of Japanese art. I took another sip of my tea, which could have been chosen to set off the room, its clean, slightly smokey aroma blending with the room’s faint odours of lemon and cardamom.

And, suddenly, of horse. I had not noticed the distant conversation cease, nor heard anyone approach, but between one breath and another there was a third person in the room, the compact, blond-haired man of the photographs, moving to greet the equally startled Holmes.

“Thank you for coming. I see Hari has brought you tea. Did he give you the Indian or the China?”

“The Indian,” Holmes answered, “and very ni

ce indeed.”

“Good. With Hari, one can never be sure. I am very pleased to meet you, Mr Holmes. We did, in fact, encounter each other long ago, when you visited my father’s camp in Himachel Pradesh, but you won’t have remembered. I was seven; my last tour with him before I went home to school.”

Holmes held the man’s hand for a moment as he studied the man’s features, and then his mouth twitched in a brief smile. “He was a district officer and you were in short trousers. A boy with a thousand questions about … turquoise and rubies, wasn’t it?”

Our host’s face opened in a grin. “I should have known you would forget nothing. And you must be … Miss Russell, I’m told you prefer? I’m Geoffrey Nesbit.”

His hand was cool and strong, and I thought, as he turned to face me fully, that Holmes’ act of memory was less impressive than inevitable: Even as a child, this would have been a difficult person to forget.

Nesbit was one of the most beautiful men I have ever laid eyes on, the thin scar running down his jaw line merely serving to emphasise his looks. Neat, blond, and sun-burnt, he was not the kind who usually stirs me to admiration, but his green eyes shone with intelligence and humour, and he watched with the quiet attentiveness of a cat, missing nothing. Like a cat, too, he appeared ageless, although the skin beside his eyes and down his throat testified to an age near forty. He reminded me eerily of T. E. Lawrence, another small, tow-headed, and youthful man who looked at the world out of the corners of his eyes, as if in constant dialogue with an amusing inner voice.

Nesbit was dressed in an odd combination of garments, jodhpur trousers beneath a long muslin kameez, and if the aura of horse he carried with him explained the trousers, he had certainly changed his footwear upon returning from his morning gallop. Unless he was in the habit of riding in soft leather slippers, in the style of an American Indian. Certainly in the photographs the man wore ordinary riding boots.

He poured himself a cup of tea, taking it black with sugar, and urged us back into our chairs, sitting down on the other side of the low, intricately carved table. He settled into a third, legs stretched out, ankles crossed.

“How is your brother?” he asked Holmes.

“Improving. I had a telegram yesterday night, he sounded himself.”

“I am glad. The world would be a lesser place without Mycroft Holmes. And a great deal less secure.”

Which observation declared, as surely as an exchange of Kipling’s whispered code-phrases, that this man knew well that Mycroft Holmes, who described himself as an “accountant” in the Empire’s bureaucracy, kept ledgers recording transactions considerably more subtle than pounds and pence. The suspicion was confirmed with his next words.

“When we have drunk our tea, we shall take a turn through the garden.” His raised eyebrow asked if we understood; Holmes’ curt nod and my reply answered him.

“We should love to see your garden,” I told him. And, clearly, to talk about those things the walls were not to hear. It was difficult to press one’s ear to a key-hole when the speakers were surrounded by open space. And the sad fact was, there were some things with which servants were not to be trusted.

So we drank our tea and passed a pleasant quarter of an hour hearing Nesbit’s suggestions about what to see during our stay in the country. He particularly urged us north, even though the weather would still be cool, and suggested one or two of the hill rajas who might show us an entertaining time.

“Do you shoot, either of you?”

I suppressed a wince: The last shooting party I’d joined had nearly ended in tragedy for the duke who was our host and friend.

“Some,” Holmes replied. “Russell here is a crack shot.”

“Of course, it’s pretty tame compared to some sports—even going after tiger from the back of an elephant pales once you’ve tried pig sticking. Or tiger sticking, although that’s harder to come by. You ever ridden after boar, Mr Holmes?”

“Er, no, I’m afraid not.”

“Is that what the Kadir Cup is about?” I asked, adding, “I noticed the photographs.”

“Yes, that’s it. Held annually, near Meerut, just north of here. Pig sticking is the unofficial sport of British India. Great fun. Though not, I fear, for the ladies.” He smiled at the thought. I smiled back, automatically plotting how I might go about learning to stick pigs—until I caught myself short. I didn’t even like fox-hunting, much less what sounded like a rout fit for overgrown adolescent boys, scrambling cross-country after a herd of panicking swine. Still, it brought up the obvious question.

“With what does one stick the pig?”

In answer he nodded towards the weaponry on the wall. “That’s the spear I took the Cup with last year.”

“The broken one?”

“Er, no. That one’s there to remind me to be humble.” He threw us a boyish grin. “Big job, that. No, the broken one’s from the ’22 Cup. The first day, I’d flushed a big ’un, run it across the fields a mile or more, right at its heels when it jinked back in a flash and came for my horse. Which very sensibly shied, dumping me top over teakettle. Somehow I landed on my own spear and took a great hunk out of my arm. Nearly the end of my career.”

“So, what, did you shoot the creature? Or did it run off?”

“Good Lord, no,” Nesbit said, affronted. “One doesn’t carry a gun when pig sticking. And once a pig’s decided to fight, it generally doesn’t quit until one or the other of you stops moving. No, one of the other fellows took the beast. And the Cup as well. Native chap—maharaja in fact, though nothing like what you think of at the title. That’s him in the photo. He nearly had the Cup from me last year, he’s that good. ’Course he should be good, he has enough practice going after any kind of game you can mention. African lion, giraffe—you name it.”

Sports; maharaja; exotic animals: The unlikely conjunction rang some bells in my mind, but Holmes got the question out first.

“What is the name of this maharaja?”

“They call him Jimmy. Rum chap, a bit, but a great sportsman. He’s the ruler of a border state named—”

“Khanpur.”

Nesbit’s eyes locked onto Holmes over the top of his cup. Then, calmly, he took the last swallow, placed the cup and saucer on the tray, and stood. “Shall we go and look at the garden?”

“Looking at the garden” seemed to be a common ritual in the Nesbit establishment. At any rate, the ground was clear for a circle of thirty yards around the two benches he led us to, benches located in the shade of a tree which had recently been thinned so its inner structure could hide no person, benches facing in opposite directions to cover all approaches. A low fountain played nearby, obscuring our voices.

“You seem to have an interest in the maharaja of Khanpur,” he said as soon as we were seated.

“Not directly, but the name has come to our attention.”

It took a while, the story. Thomas Goodheart and the bison-collecting maharaja who had been at a Moscow gathering attended by Lenin. The defiant words of the drunken Goodheart, and his odd choice of fancy dress, preceded the odder decision to enter Aden with a debilitating hang-over on the day a balcony fell. To say nothing of the interesting coincidence that Khanpur was one of the kingdoms along the northern borders insulating British India from her long-time Russian threat. Holmes even mentioned my missing trunk, although by this time neither of us thought that was due to anything more sinister than inefficiency, or at the most a garden-variety thievery.

Nesbit listened without comment, but with such intensity that I thought he might well be able to recite Holmes’ words verbatim afterwards. At the end, he sat forward with his elbows on his knees, his eyes not seeing the playing fountain while his mind explored the information. Eventually, he sat upright.

“If Goodheart is a known Communist, we probably needn’t worry, although I’ll pass his name on to the political johnnies. As for Khanpur, the state has always been staunchly loyal to the Crown. During the Mutiny, a handful of sepoys fleein

g north attempted to pass through the kingdom, carrying with them two English captives, a mother and her young daughter. The then raja, Jimmy’s grandfather, allowed them entrance, but then set up an ambush on the road that passes through two halves of his hill fort. Dumped a thousand gallons of lamp-oil down the hill and set it alight. Killed them all, including the woman, unfortunately, but the child lived and was returned home. By way of recognition of their service, all the Khanpur tribute is remitted annually. And the raja’s rank was raised to maharaja. Khanpur has a seventeen-gun salute, which is big for its size—the girl’s family was important.”

“The Mutiny was a long time ago.”

“The Mutiny was yesterday, as far as every white man in the country is concerned. But it is true, that was the grandfather, and much can change in sixty-seven years. I shall bring this to the attention of my superiors.”

His eyes came back into focus. “Now, as to the reason why you are here. Kimball O’Hara. Mr Holmes, you knew O’Hara, did you not.” It was not a question.

“When he was a boy.”

“By all accounts, the man he became was there from the beginning.”

“The lad was remarkably well suited to The Game,” Holmes agreed.

“Which makes it all the more troubling that he has vanished.”

“How long has it been since he was last heard from?”

“Just short of three years.”

“Three—” Holmes caught himself. “We were told that he had not worked for the Survey in that time, but I had the impression his actual disappearance was considerably more recent than that.”

“It’s only in the past months that we’ve become aware of it. But once we cast back to look for his tracks, the last sure sighting we could come up with was in August of ’21.”

“Where was that?”

“In the hills above Simla. He stopped the night with an old acquaintance, and told her that he was going back to Tibet for a time, although he intended a detour to Lahore first to visit a friend.”

O Jerusalem

O Jerusalem Beekeeping for Beginners

Beekeeping for Beginners The God of the Hive

The God of the Hive The Language of Bees

The Language of Bees Night Work

Night Work Justice Hall

Justice Hall The Murder of Mary Russell

The Murder of Mary Russell Lockdown

Lockdown To Play the Fool

To Play the Fool Locked Rooms

Locked Rooms Island of the Mad

Island of the Mad The Art of Detection

The Art of Detection The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4 The Beekeeper's Apprentice

The Beekeeper's Apprentice For the Sake of the Game

For the Sake of the Game A Darker Place

A Darker Place Mila's Tale

Mila's Tale Mrs Hudson's Case

Mrs Hudson's Case With Child

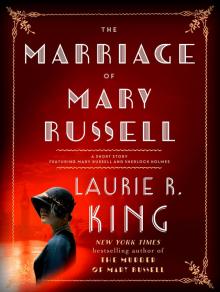

With Child The Marriage of Mary Russell

The Marriage of Mary Russell The Mary Russell Companion

The Mary Russell Companion Hellbender

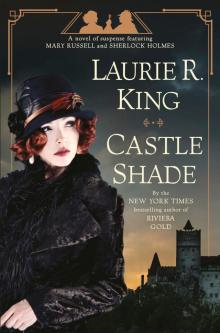

Hellbender Castle Shade

Castle Shade The Bones of Paris

The Bones of Paris Riviera Gold

Riviera Gold A Grave Talent

A Grave Talent Pirate King

Pirate King Dreaming Spies

Dreaming Spies Folly

Folly Touchstone

Touchstone The Game

The Game The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor

The Mary Russell Series Books 1-4: The Beekeeper's Apprentice; A Monstrous Regiment of Women; A Letter of Mary; The Moor The Moor mr-4

The Moor mr-4 The Birth of a new moon

The Birth of a new moon With Child km-3

With Child km-3 A Letter of Mary mr-3

A Letter of Mary mr-3 Justice Hall mr-6

Justice Hall mr-6 Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11

Pirate King: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes mr-11 Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story)

Beekeeping for Beginners (Short Story) Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes

Laurie R. King's Sherlock Holmes Echoes of Sherlock Holmes

Echoes of Sherlock Holmes A Study in Sherlock

A Study in Sherlock The Game mr-7

The Game mr-7 Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Garment of Shadows: A Novel of Suspense Featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes

Dreaming Spies: A novel of suspense featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes Night Work km-4

Night Work km-4 Mary Russell's War

Mary Russell's War To Play the Fool km-2

To Play the Fool km-2 A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2

A Monstrous Regiment of Women mr-2 O Jerusalem mr-5

O Jerusalem mr-5 A Grave Talent km-1

A Grave Talent km-1